Crazy ideas help researchers grow. And that's not so crazy.

Jerry Simmons walked into Sandia Labs 26 years ago, hired for a program that didn’t exist. His job was to take Sandia into nanoelectronics. Searching for a start, he proposed a Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) project on electronic interactions between closely spaced semiconductor quantum wells. “That work grew into a wide range of activities, from single electron transistors to Coulomb drag to high-mobility molecular beam epitaxy growth,” Simmons says.

Sound wild? It is. But that ’s what LDRD allows scientists to do. “You can take a chance on a crazy idea, which may end up being not so crazy after all,” Simmons says. And, along the way, scientists get better.

Simmons is a rock star, one of four active Sandia Fellows whose lists of professional accomplishments fill pages, lifting them into the elite ranks of people who are figuring out how the natural world works. “LDRD has played a crucial role in my career, from day one to the present,” Simmons says. “It ’s no overstatement to say it is the lifeblood of the laboratory.”

LDRD was established by Congress in 1990 to fund forward-looking, high-risk, potentially high-payoff research at the national laboratories. The goal was to build a vital research environment that rewards innovation, builds skill and produces breakthroughs, pushing the frontiers of science and technology. “LDRD infuses the laboratory culture with a reverence for curiosity and a respect for pioneering discovery,” Simmons says. “This is how we take leadership in a field, by being the first to get into something no one else has bought into yet.”

The investment pays off

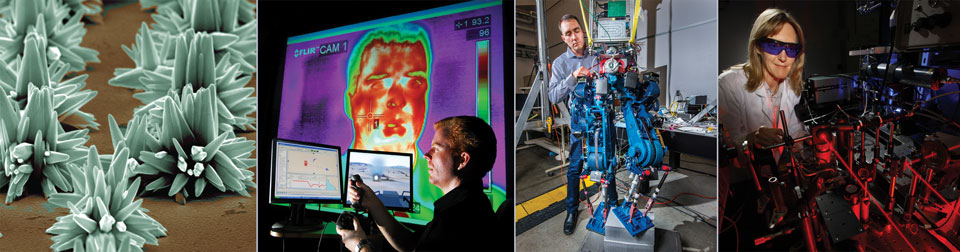

At Sandia, LDRD is funded as a percentage of all the programs that come into the labs, and is at just under 6 percent, or $155 million a year, for fiscal year 2016. The investment has paid off with important scientific advances across an array of disciplines from bioscience and computing to microsystems and geoscience. LDRD projects, awarded through a rigorous, highly competitive peer-review process, align with the labs’ core national security mission while taking science to new and extraordinary places. LDRD-funded projects have contributed to every facet of Sandia’s national security mission, including stockpile stewardship, highenergy- density matter, computing and simulation, materials science, chemistry, biosecurity, cybersecurity and energy. Many Sandia programs, such as radiation-hardened electronics and solid-state lighting, have roots in research that began in LDRD. Projects funded by the program have earned national recognition through awards, including many R&D 100 awards, papers and patents.

Andy McIlroy, deputy chief technology officer and director of Sandia’s Research Strategy and Partnerships Center, says LDRD helps Sandia and other national labs attract and keep the best scientists and engineers. “We hire exceptional people and we want to give them the opportunity to use their genius and creativity to find new ways to solve problems,” he says. “The research freedom offered by LDRD can launch a scientist to another level of accomplishment.”

The National Research Council of the National Academies says LDRD “is critical for attracting and retaining high-quality technical staff and thus for assuring long-term viability of the laboratories and their ability to carry out their mission in the future.” The council went on to say that “the novel and innovative approaches supported by LDRD are essential to the nuclear weapons mission.”

An early career boost

The LDRD program develops researchers in a variety of ways. From 2009 to 2016, one element invested in early careers and was used to help bring promising young people to the labs. “A manager would meet someone at a conference or hear a great student paper and think that ’s the kind of person we want,” McIlroy says. “But they were looking for jobs right then and the manager didn’t have funding for a position. Early Career LDRD gave managers the confidence to bring sharp people in before they took other jobs, and get them started.”

More than 200 researchers participated in that program, which is ending in 2016. The overall LDRD program continues to encourage support of early career researchers. “At the start of their professional life, they can have their own LDRD projects,” McIlroy says. “And those projects lead to others, building momentum.”

A 2015 report by the Secretary of Energy Task Force on Department of Energy National Laboratories said, “For the NNSA [National Nuclear Security Administration] laboratories in particular, LDRD provides a way to maintain a pool of talented individuals whose work is aligned with the core mission of the laboratories. This finding is supported by evidence of the participation of early career staff and recently recruited staff in LDRD programs.”

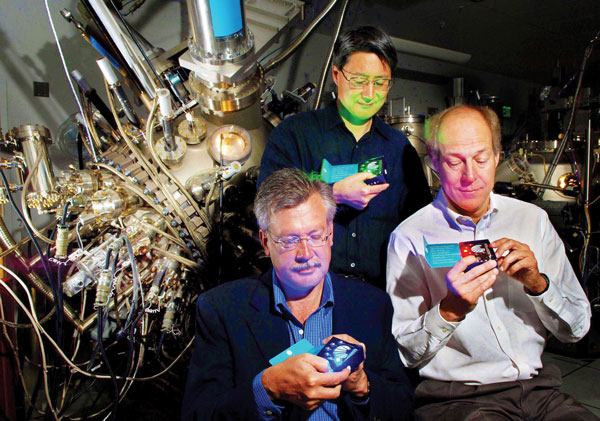

The program also builds leadership skills. “The principal investigator on an LDRD project must put together a team,” McIlroy says. “They have both technical and leadership responsibility. Other people on the team also take on leadership roles.” LDRD projects can involve a few people to 20 or Solid-state lighting pioneers, from left, Jerry Simmons, Jeff Tsao and Michael Coltrin have seen their work contribute to the widespread consumer use of light-emitting diodes, or LEDs, an alternative to incandescent bulbs. Sandia R E S E A R C H more in a Grand Challenge, which is a larger LDRD project that focuses on bold, high-risk ideas with potential for significant national impact.

Problems nobody has thought of

“LDRD offers people an opportunity to grow,” McIlroy says. “It goes back to creativity and innovation. It gives them another way to contribute to the scientific community and national security. LDRD plays a key role in building and sustaining Sandia’s foundation.

Another piece of LDRD is the Truman Fellowship program for distinguished postdocs, named after President Harry S. Truman, who charged Sandia in 1949 with providing “exceptional service in the national interest.” Sandia reaches out nationwide for applicants for the three-year fellowship, and extends offers based on mentorship and interviews by senior scientists. “We look for the rising stars, people who have just earned their doctorates and have the potential to change the world,” McIlroy says. “We want to give them the opportunity to reach their potential while serving the nation.” Sandia has had 22 Truman Fellows since the program began in 2005, many of whom still work at the labs.

And Sandia’s four active Fellows — Jeff Brinker, Ed Cole, John Rowe and Simmons — have LDRD funding they can use for their own research or to fund other people. “As mature and exceptional researchers, they can use these funds to seed critical advances for the labs’ future,” McIlroy says. “They can identify new researchers, recognize high potential ideas and they can fund their own ideas.”

Simmons says his role as a mentor to young researchers through LDRD projects has kept him engaged in the wonder of discovery. “LDRD plays a multitude of roles throughout the career of a scientist,” he says. “First it helps new people get a toehold and establish a research program. It ’s essential for recruiting and retention. Later, LDRD supports our most innovative and revolutionary ideas. And Grand Challenges let Sandia put together large interdisciplinary teams to tackle the biggest problems.” Simmons says that in his more than two decades at Sandia he’s seen “a lot of really innovative ideas grow from hallucinations to impactful technologies.”

“LDRD is important for the long-term health of the institution if we are to transform the products we deliver to our national security customers,” he says. “Without it, the labs would be a different place. These crazy ideas don’t always pay off, but when they do, it ’s fantastic — for everyone involved.”