While significant asteroid impacts on Earth are rare, the ones that have landed have left a mark. There’s the one that killed the dinosaurs, for starters. More recent impacts left craters in eastern Siberia and eastern Arizona. Videos immortalized on the Internet in February 2013 show a flaming meteor whizzing toward Chelyabinsk, Russia. The resulting explosion burst windows, damaged buildings and sent residents running for cover.

Since 1998, NASA has been mapping all the comets and asteroids within 30 million kilometers of Earth. As the map fills in, it’s clear that this area is a very busy place.

“It’s the luck of the draw we’re not hit,” said NASA Planetary Defense Officer Lindley Johnson. There are about 21,000 asteroids in the count so far, 900 of which are greater than 1 kilometer in size. That’s only one-hundredth the size of the dinosaur-killing asteroid, but still large enough for an impact to have global effects. “This stuff is whizzing past all the time,” Johnson said.

While no known large asteroid poses a significant risk of impacting the Earth in the next century, geologic evidence shows that the potential hazards from an impact cannot be ignored. Johnson leads NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, which organizes national and international efforts to predict and mitigate hazards from an asteroid hitting the planet. The PDCO tracks the orbits of asteroids near Earth with ground- and space-based telescopes, works with international colleagues to craft emergency response plans and develops ways to deflect objects in space years before they’re on an irreversible collision course with the planet (see sidebar).

While their mission seems straight out of a Star Trek episode, the office’s daily work requires sophisticated engineering, modeling and detection, some of which directly involves Sandia expertise. Johnson, along with colleagues from NASA’s Asteroid Threat Assessment Project, including Sandia researcher Randy Longenbaugh, spoke in Albuquerque in October about the challenges of defending the planet from an asteroid impact.

Asteroid entry

NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations program has identified almost all of the asteroids larger than 1 kilometer orbiting near Earth. This mapping has eliminated 96% of the risk of sudden, unexpected impact from an unknown large asteroid. Yet more than two-thirds of near-Earth asteroids 140 to 300 meters in size are still unmapped, Johnson said. These objects are at least 60 times larger than the meteor that hit near Chelyabinsk; an impact could generate a tsunami, a shock wave and a blast of heat.

To better understand what effects could be felt on the ground after an asteroid impact, ATAP, sponsored by the PDCO, is working to refine models of asteroid entry so they can extend those conditions to potential ground hazardous effects.

At first, asteroid entry seemed like a straightforward application for existing modeling of hypersonic spacecraft entry, said Eric Stern, ATAP entry modeling lead. “We quickly learned it’s not as easy as you might hope.”

The first difference is that the material that comprises asteroids melts during atmospheric entry, and unlike spacecraft, loses mass through the flow of liquid on the surface, Stern said. Also, much of the mass of an asteroid can vaporize during entry, and the vaporization products emit light that complicates interpretation of luminosity-based observations of an asteroid’s speed and energy.

Very large uncertainties interpreting luminosity combined with sparse data from the few real-world impacts observed make it very difficult to validate predictions. But with a few tricks, existing tools can help.

Stern and his colleagues took a sample of a meteorite to NASA’s Arc Jet Complex, an experimental test facility that generates an extremely hot atmosphere to test materials and develop models for spacecraft reentry. High-speed footage of material melting and vaporizing from the meteorite combined with infrared and spectral imaging of the vaporized meteorite components provided data that helped them refine their models of ablation and composition.

Another way to learn about the composition and entry of large asteroids is to track smaller ones that enter the atmosphere every few weeks as fireballs. For approximately 15 years at Sandia, Randy worked with Dick Spalding and Joe Chavez to detect fireballs, or bolides, using ground-based cameras and space-based sensors, including some developed at the Labs.

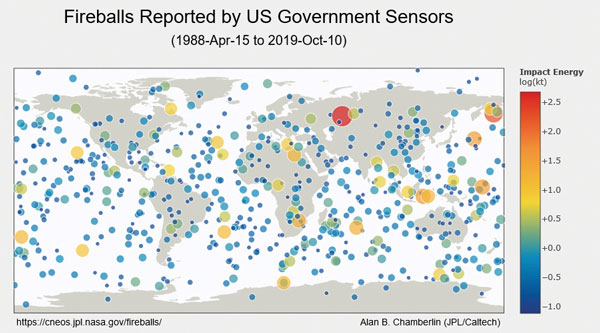

“Observing bolides provides the best data to understand the composition of small asteroids and how they disintegrate in the atmosphere,” Randy said. NASA uses data from sensors to record the disintegration of small asteroids when they hit Earth’s atmosphere. A map produced from a limited amount of data from these impacts shows the impact locations marked with a dot proportional to the kinetic energy released during the impact. Combining various sensor data, this map is used to report geographic location, altitude of the disintegration, velocity and velocity components and the total radiated energy.

Randy is continuing his work on bolide detection while on temporary assignment at NASA Ames. As ATAP observational entry data lead, he is also working on real-time automated fireball detection, as well as bringing other types of Sandia sensing work to the project.

Temporary assignment

As a national laboratory and a Federally Funded Research and Development Center, Sandia is uniquely positioned to loan employees to federal agencies, congressional assignments or other partner institutions. Depending on the type of assignment, Sandians can temporarily act like federal employees or technical consultants; they can also perform a Sandia project at another institution.

After meeting Johnson and learning of the PDCO, Randy wondered if he might be able to do a sabbatical at NASA. At the same time, Johnson was interested in increasing PDCO’s asteroid detection and characterization work.

Using the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, Randy has been able to work at NASA Ames for the past two years. He remains a Sandia employee, and is also granted temporary authority to act as an employee of NASA Ames for his three-year assignment. This is the first IPA Sandia has had with NASA in this type of work.

“It’s been an incredible and very rewarding experience,” Randy said. He has enjoyed working with colleagues based nationally at NASA and other federal agencies, as well as internationally. “It’s also given me an opportunity to help a sponsor build a program, and I hope it creates new opportunities for Sandia too.”

To learn more about offsite extended duty assignments, contact Sandia’s Offsite Extended Duty Assignments Program office.

Double Asteroid Redirect Test

Currently, an asteroid impact is the only potentially preventable natural disaster. Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer at NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, described three options for changing the path of an incoming asteroid: slamming something into it to change its velocity (the kinetic impact option), dragging it off its path using a gravitational attraction (the gravity tractor) or detonating a nuclear device nearby to push an asteroid off its orbit (the nuclear option).

“The nuclear option may be the only choice if time is short or the object is very large, but there are obvious international treaty issues with that,” Johnson said.

The PDCO is developing its first mission to test the kinetic impact option. Called the Double Asteroid Redirect Test, DART will launch in September 2021, headed toward the moon of an asteroid called Didymos. The craft will slam into the moon a year later, disrupting its orbit without altering the orbit of the entire asteroid system.