Dr. Yvonne Cagle, astronaut, surgeon, retired U.S. Air Force colonel and aerospace researcher, has developed a device for space flight that heals muscle damage in record time here on earth.

The technology can transform an ankle from sprained to strong in mere minutes instead of weeks. Cagle attributed her success to the foundation built by black innovators at NASA, saying she is a passionate advocate for diversity in the workplace.

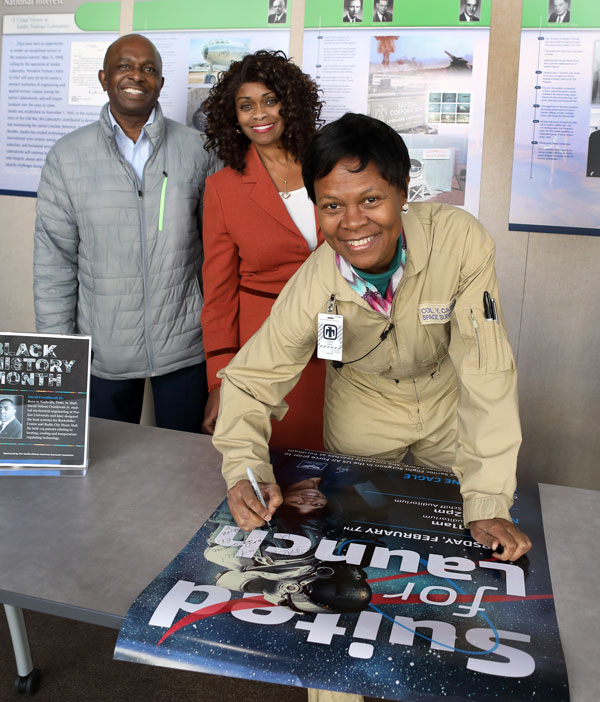

Cagle spoke at Sandia/California as part of Sandia’s Black History Month events.

Traveling in space

Cagle began her talk by describing the feeling of space flight. You never actually see your first launch, she said, you feel it. The vibrations are so strong you have to clench your eyes shut. Once you arrive in zero-gravity, however, she said it feels like skating on glass.

More significant, she said, are the physiological effects of being in space. Scientists have a lot to learn about how bodies behave in space, and Cagle wants to know more about what happens to human health should we attempt to permanently relocate populations off the planet.

It is possible that space travel, whether short or long term, could change living beings radically, even genetically. The possibility prompted Cagle to wonder, “What if the alien we’re in search of is ourselves?”

The fate of floating bodies

The constellation of nasty health symptoms that some astronauts suffer is known as Space Adaptation Syndrome. These negative adaptations to space travel — facial swelling, foggy thinking, a confused sense of balance and direction, nutrient loss, muscle atrophy and bone density loss and demineralization — can continue to cause problems even after astronauts return to Earth.

Keeping muscles healthy is a big focus of Cagle’s current research. Muscle injuries heal more slowly when muscles aren’t moving against gravity and aren’t being exercised. To combat this, she created LIFT, a wearable device that enables rapid healing of strained or sprained soft tissue.

The device takes water produced by inflammation and generates electric currents that restore and rebalance the damaged soft tissue. Cagle showed the audience a photo of a badly bruised and swollen ankle, and then a picture of the ankle after using the device. No trace of bruises or swelling remained.

There was an audible gasp in the room when Cagle revealed the entire healing process had taken a total of 10 minutes.

Space for all

Cagle noted that hers is only one of many exciting innovations made possible by spaceflight research. However, she said the NASA space program would not have evolved, with aspirations of traveling to Mars, without the efforts of her friend and mentor Katherine Johnson.

Fifty years ago, Johnson’s space flight calculations helped the first humans to walk on the moon. Seven years prior, the astronaut John Glenn had insisted that Johnson help verify by hand the equations that would control the trajectory of his historic earth-circling mission.

Johnson’s work as a “human computer,” as well as the work of two other female African-American NASA pioneers, was celebrated in the film Hidden Figures, nominated for three Academy Awards in 2016.

But Cagle lamented that today there are still too many hidden figures whose work is neither acknowledged nor encouraged. She said she is a champion for diversity and inclusion because corporate cultures that invest in diverse voices breed deeper understanding of and compassion for all people, encouraging success.

“There is space for all,” Cagle said, “And with diversity and inclusion, the possibilities are endless.”

A community grassroots effort

Cagle’s trip to Sandia started with Camron Proctor, a systems engineer in thermal fluid science.

“Over a year ago, Camron came to me with a very compelling case for bringing Dr. Yvonne Cagle to speak at Sandia regarding her work and the topic of diversity and inclusion in the workforce,” said Kayla Norris, team lead for the diversity and inclusion speakers series and Sandia/California’s community relations officer. “After researching her accomplishments and watching some of her TedX talks, I was completely on board, as was Sandia’s African American Outreach Committee.”

For six months, Kayla tried to contact Cagle without success. When Cagle gave a talk at Harvard University, Kayla worked through the university to issue the invitation and confirm that Cagle could speak at Sandia.

Working with Jenessa Dozhier and Tony Baylis, who lead diversity and inclusion efforts at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the African-American Body of Laboratory Employees at the neighboring lab enthusiastically agreed to help bring Cagle to Sandia.

After her talk, Cagle had lunch with many members of the two outreach groups and met with Cathy Branda, senior manager for applied biosciences and engineering, Camron, Kayla, and Jasmine King-Bush, co-chair of the Division Diversity Council.