Sandians share their stories, photos about August 21 total eclipse

‘The shortest two-plus minutes of my life’

See also “Whoops of elation then awestruck silence”

By Paul Schmit

I was one of the Sandians who ventured out on August 21 to witness the total solar eclipse that crossed the country. After several weeks of planning and several hours of driving, I navigated to a very particular site in west-central Wyoming in pursuit of a very specific photograph.

There, along just a single mile of US Highway 287, just north of the small town of Crowheart, Wyoming, was the only location across the entire country that offered two unique observational opportunities in one place. First, during the early stages of the partial solar eclipse, there was an opportunity to photograph the International Space Station crossing the disk of the sun at the same time the moon was moving into view. The transit was set to occur at 10:43:55 local time, and the entire event would take less than a single second to transpire. Second, this same spot coincided with the centerline of the moon’s path of totality, meaning one could also experience the full two-minute-plus duration of the total eclipse, some 50 minutes after the ISS transit.

I am happy to report that I was successful in both ventures, documenting the ISS transit and the full extent of totality. I was intrigued by a couple other photographers who also managed to capture the ISS transit, both of whose photographs were quickly picked up by the New York Times and other major news outlets by that evening. Interestingly, in those cases, the photographers were apparently elsewhere, one in northernmost Wyoming, the other in Washington state, both outside the path of totality. As far as I can tell, I might be the only person to document the ISS transit while still enjoying the spectacle of the totality from the same vantage point. I am especially grateful to my colleague, Thomas Mattsson, who provided lodging less than an hour from my prospective vantage point the night before the eclipse.

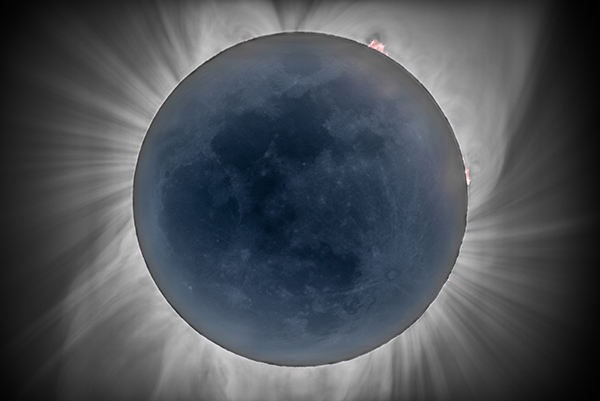

The eclipse experience itself was packed with sensory delights. The overpowering brightness of the late morning sky slowly gave way to an almost disturbingly uniform dimness, not like a cloudy day, but more as if I were squinting in broad daylight to look in every direction. The buzz of bees in the fields adjacent to the highway eventually went silent, and in the few minutes immediately prior to totality, swarms of gnats and chirping crickets took their place. As the sun diminished to a tiny sliver, the ambient light became warmer and my dim shadow grew astonishingly crisp, while long, thin streaks of diffuse shadows appeared seemingly out of nowhere and raced across the gravel shoulder toward the horizon. The sky began to resemble dusk, with a faint orange glow on the western horizon until, suddenly, I realized I could see this glow in every direction. Totality had arrived, and with it came the wondrous view of the sun’s tenuous corona reaching far out into the solar system. Its haunting beauty evoked a sense of profound vulnerability, as it became immediately apparent that we on earth are not isolated from our sun’s expansive ethereal grasp. Distant planets and a few bright stars appeared above as cheers erupted from other observers scattered across the otherwise desolate highway. The limb of brilliant white light surrounding the moon’s silhouette appeared to be adorned with flecks of orange and red, which photographs later revealed to be earth-sized solar prominences erupting from the sun’s surface.

My jaw hung open for nearly the entire duration of totality (I have video evidence to prove it), and after the shortest two-plus minutes of my life, the entire event repeated in reverse order, as the orange glow of daylight began to encroach on my location once again. One more glimpse of the ghostly shadow bands racing along the highway marked the conclusion of one of the most awe-inspiring natural spectacles I have ever observed.

Whoops of elation then awestruck silence

By Dan Riley

As a photovoltaics engineer, a key part of my job is measuring solar radiation. And as you’d expect, an interest in all things solar is a natural outgrowth of the job.

I’d found the 2012 annular eclipse that was visible here in New Mexico interesting, but I’d read that a total eclipse is in a class to itself. So, about 18 months ago, when I learned that a total solar eclipse would occur in the continental US for the first time in 38 years, I knew this was something I couldn’t miss. I began to make plans to see it. On Aug. 18, I packed my three oldest children (10, 8, and 6) in the car and we headed for central Missouri, directly under the umbra (shadow) of the moon.

I’d planned meticulously: I’d rented a very long camera lens, I’d ordered viewing glasses months ago, and I’d plotted out five potential viewing locations across the state of Missouri in case of heavy cloud cover. Yet, on the eve of the eclipse, I still felt very nervous about the next day. I was just north of Jefferson City, which had a forecast of 50-60 percent cloud cover, not ideal viewing conditions. Forecasts to the northwest were even worse. Late on the 20th, I decided to go to my backup location to the southeast, St. Clair, where a friend of my aunt was hosting an eclipse viewing party and forecasts predicted only 30-40 percent cloud cover. That looked to be my best option.

As we drove through downtown St. Clair (population 4,700) on the 21st, it was clear that the eclipse was a very big deal. Non-Missouri license plates outnumbered Missouri plates 3 to 1 and businesses were charging $5 to $10 to park in their lots. We arrived early and set up lawn chairs, cameras, and the irradiance measurement equipment I’d brought along. The kids ate Moon Pies and Sun Chips, successfully avoiding eating anything of nutritional value while I was preoccupied with equipment and taking photographs.

About an hour before the eclipse began, a layer of high clouds threatened to foil all my plans, but thankfully they had mostly cleared out by the time the eclipse started. As totality approached, the anticipation was very high — even my children were excited as the sun became a tiny sliver peeking out from behind the moon.

There is an eerie feeling when totality is near. It’s tough to pinpoint the cause of the strangeness, but there is a vague unease as the midday twilight quickly turns to total darkness.

When the long-anticipated moment arrived, the entire party wondered at the marvel of the total eclipse. Whoops and cries of elation rang out all around as observers cheered the arrival of totality. These cries quickly died down as we shifted focus to the perfect ring of light. Most of the adults then stared in near silence, while children repeatedly yelled, “That is so cool.”

When viewed by eye, the coronal streamers didn’t stretch as far as I’d seen in pictures, but they were beautiful nonetheless. I snapped as many pictures as I could over a wide range of shutter speeds while trying to simultaneously view and remember the sight.

During an eclipse, the focus of interest is on the sun and moon, but there are other points of interest, too. Venus could clearly be seen, and there was a definite glow on every horizon. For that wonderful 2.6 minutes, we almost felt we were in a different reality. Totality finished entirely too soon but for a minute after totality we could view shadow bands on the ground caused by turbulence in the atmosphere creating a fluctuating lens for the slim crescent sun. As the eclipse continued after totality, we watched the second partial phase, although with much less enthusiasm since the real spectacle had already occurred.

There was broad consensus from our group that the eclipse had easily lived up to the considerable hype and by the end of the cosmic event I had already decided that I would see the next US-crossing total eclipse in April 2024. The 2024 umbra will trace a path northeast from Dallas to Indianapolis, over Lakes Erie and Ontario, finally leaving the US through Maine. And next time, my entire family will certainly be traveling to enjoy this rare and beautiful event.