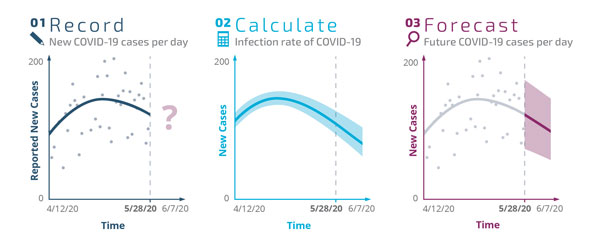

Short-term predictions match outbreak data

Global data networks that connect people through their devices have made it possible to create accurate short-term forecasts of new COVID-19 cases using a method pioneered by Sandia researchers Jaideep Ray and Cosmin Safta.

Jaideep and Cosmin used a model developed more than a decade ago to track plague epidemics using statistics. For COVID-19, the two also drew upon the advice of their Sandia co-workers with expertise in modeling, mathematics and software engineering.

“I first started using this method in 2008-09. Cosmin and I adapted it in 2010 to track influenza-like illnesses,” Jaideep said. “When COVID-19 began to spread so rapidly, we knew we could use the same method to help forecast the outbreak.”

He and Cosmin use publicly available data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the New York Times Data Repository, Johns Hopkins University and various state departments of health. Within minutes, and without the need for high-performance computing resources, the researchers can forecast new cases in a region or nationally for the next seven to 10 days. Since April, the number of new cases has roughly followed the trends predicted by the team.

“This method is a relatively easy and inexpensive way to get short-term forecasts about new coronavirus cases that decision-makers can use to allocate health care resources and response,” Cosmin said. “This method is much easier and cheaper to do than methods that require more robust computers and manpower.”

Accuracy over time

The range of accuracy for the predictions varies with the number of days out the researchers are trying to forecast. So, while the number of cases has generally followed the trends predicted in the model within a week or so, the method is not useful to predict more than 10 days out.

“The forecasts come with a range within which users can expect reality to lie,” Jaideep said. “The range changes daily depending on the data, but the model ensures that the user can have 95% confidence that reality will fall within the range.”

The project, funded through Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program, provided national results to the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory team for publication on a DOE-run dashboard (funded by the DOE Office of Science) for federal decision-makers. Specific results also were provided to the New Mexico Department of Health, to guide regional responses throughout the state.

The data revealed by the forecasts can also gauge the impact of interventions over time. Both researchers say responding quickly to provide data on emerging outbreaks would not have been possible even five years ago.

“Since we are so connected today, it’s possible to get an accurate number of COVID-19 cases in a day and get it to everyone in the world within a 24-hour period,” Jaideep said. “Ten years ago, even five years ago, you could not get this data. In 2015, with the Ebola outbreak, by the time they got data, it was pointless to try and make a forecast because it was already out of date and useless to decision-makers.”

“For the current COVID-19 situation, having more sources of data dramatically assists our ability to create short-term forecasts to inform public health decisions,” Cosmin said.