Retired Sandian’s work comes full circle at 75th Anniversary celebration

In 1976, Andrew Rogulich began what would be a decades-long career at Sandia.

It was the year Jimmy Carter was elected president. The year Apple Computer was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. It was the year iconic songs “Turn the Beat Around” and “Fly Like an Eagle” came out.

When he started out, Rogulich, 69, couldn’t have guessed that technology he worked on in the ’70s would become part of the official record of Sandia’s 75 years of history and create one of the most gratifying experiences of his career.

The year of 1976 was an all-around different time in the nation and the Labs was no exception. The campus was nowhere near the size that it is today; Rogulich remembers everything east of Building 880 was “just dirt.” If he needed to look something up, he didn’t have a computer on his desk waiting to Google his every inquiry; he’d have to go to a design information center and look it up on microfilm or microfiche. The workforce population was less than half it is now with 7,022 members compared to the 16,825 people currently working at the Labs.

“One of my very close friends I made at Sandia once told me he was employee number six (hired at the Labs),” Rogulich said.

Rogulich came to work with some of the very first Sandians after graduating from DeVry University in Chicago where he studied electrical engineering. If you asked him then where he’d end up, he would have said Los Angeles or somewhere west. But a Sandia recruiter visiting DeVry told 20-year-old Rogulich about Albuquerque, New Mexico, and the important work happening there — altering his course entirely.

“I had no idea what Sandia National Labs was. The only thing I knew about Albuquerque was what I learned on ABC Wide World of Sports,” he said, remembering a segment on the dirt racetrack that was just south of the Innovation Parkway Office Center.

Rogulich wanted to make a difference with the surety of possibility reserved for new college grads. So, he heeded the word of the recruiter and moved to Albuquerque, starting work at Sandia on Jan. 19, 1976, as a technical staff associate.

For Rogulich, that surety never faded. In fact, it quickly grew as Sandia’s mission became his vocation.

“When I was 20 years old, I told my coworker: ‘This work is so important that I will make it my personal commitment to give 50 years to government service,’” Rogulich said.

He’s one year shy of his goal with 34 years at Sandia and 15 years at the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center.

Saving interface

Those 49 years have brought many points of professional pride but none more than his work on technology that was included in Sandia’s 75th Anniversary celebration on Oct. 31.

Hundreds of people came to the celebration in front of Building 800 to watch Historian Rebecca Ullrich remove floppy disks, heaps of paper, video tapes, an array from the Z machine and more from a time capsule sealed 25 years prior. Meanwhile, Rogulich attended with his eye out for a small blue device called the SMU-105/C Interface Simulator.

In 1979, Rogulich was the systems engineer on the nuclear weapons simulator project after the German and Italian governments needed a handheld device that could simulate the cockpit responses of nuclear weapons for aircraft crews’ training. The standard at the time was developing a full-up weapon shape that would have to be loaded up on the aircraft, released and refurbished. The German and Italian militaries wanted something small and lightweight, and Sandia had to figure out how to make that happen.

“As a systems engineer, I was in charge of designing what this thing was supposed to look like,” Rogulich said about the project that took from 1979 to 1981.

The simulator is a device used for military nuclear weapon delivery training and aircraft compatibility testing, simulating the electrical logic interface of a variety of nuclear bombs with aircraft responses identical to those of true nuclear weapons, Rebecca said. It also happens to be the perfect size for a time capsule container.

In 1999, when former Labs Corporate Archivist Myra O’Canna was tasked with finding artifacts for Sandia’s 50th Anniversary time capsule, she had to find compact, unclassified and quintessentially Sandian items to include. Rogulich thought the SMU-105/C Interface Simulator fit the bill, seeing it as representative of Sandia’s work before the new millennium while remaining relevant far into the future.

“I put in (a simulator) that works because I was confident it would still be in use by the time we open the time capsule,” he said.

On Nov. 1, 1999, Rogulich watched as the 50th anniversary time capsule — with the simulator nestled inside — was lowered into the ground in front of Building 800, which is where it sat for two and a half decades.

In those 25 years, Andrew spent about 10 more years at Sandia, climbed the ranks to principal member of the technical staff, got married and had children. After retiring from Sandia on a Friday, he went to work at the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center on the next Monday.

Another 15 years of driving through the Kirtland Air Force Base gates, hopping on work meetings and meeting deadlines zoomed by until his daughter, who is now a mechanical engineer at Sandia, told her dad about the 75th Anniversary celebration, which included the opening of the old time capsule.

Full circle

While some say 25 years is hardly enough time for a time capsule to lay dormant, Rogulich saw it as a cyclical moment he otherwise never would have had.

“It was like going full circle,” he said. “You never think you are going to be old enough to see something you put into a time capsule be taken out.”

Yet again, he sat in the crowd in front of Building 800 — this time on an unseasonably warm fall afternoon in 2024 – to watch Rebecca take artifact after artifact out of the container, eventually pulling out the sky-blue simulator.

Rogulich was right. The devices are still in use today as a nuclear weapon delivery training device by the U.S. and NATO since 1983, according to Rebecca.

“What a sense of fulfillment,” he said. “All the guys I worked with are long gone but the legacy of their hardware lives on.”

It’s hard not to get sentimental when such a definitive marker of time presents itself like the time capsule did.

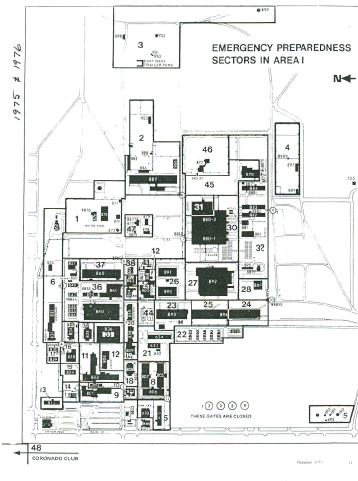

Rogulich thinks about how he liked to grab lunch at the Coronado Club, a hot spot and Sandian favorite that opened on base in the ’50s. He reflects on how different his first day on the job was compared to the modern new employee orientation. His inaugural day consisted of getting a badge, being shown where the bathroom was and told to jump right in with on-the-job training.

Overall, he thinks about how quickly time went from being a systems engineer working on the SMU-105/C Interface Simulator project, eager to solve a global problem, to a veteran Sandian coming back on campus to watch his work hoisted out of a memento designed to be emblematic of the past.

“The first 30 years go by real fast,” he said. “I would tell Sandians today to enjoy the time they have because they will look back and see just how fast their career really went.”