For 30 years, Sandia’s Dennis Roach piloted commercial aircraft safety program

Imagine in the early days of a new job, fresh out of college, your manager asks you to take on a colossal task of global consequence — developing a program at Sandia to ensure the airworthiness of commercial aircraft, independent of the airline industry and supported by the Federal Aviation Administration.

Dennis Roach, a newly minted aerospace engineer at Sandia, was just easing into his role in the Labs’ modal analysis group analyzing structural dynamics tests.

“I happened to cross paths with the manager who hired me,” he said. “He was attempting to stand up an airworthiness assurance program and asked for my help.”

Sandia had already earned national recognition for ensuring the reliability of high-consequence systems and critical assemblies across multiple disciplines, Roach said. Recognizing this, the Federal Aviation Administration approached the Labs to help ensure the long-term safety of commercial aircraft. Thus, the Federal Aviation Administration Airworthiness Assurance Center, or AANC, operated by Sandia took flight.

Tinker tot

Growing up in a small town in Upstate New York with three older sisters, Roach was influenced early on by his father, a chemical and materials engineer. “Just watching and listening to him talk about his work probably started my interest in engineering,” he said.

As a kid, he enjoyed building things with Tinker Toys and erector sets. Then, as sports became a bigger part of his life, his bicycle turned into his primary mode of transportation for baseball and basketball games and hanging out with friends.

“We lived on our bikes and were grateful for the independence that came with them,” Roach recalled. What does a burgeoning engineer do with such a prized gift of freedom? “We started taking our bikes apart and customizing them and then we built go-karts and minibikes.”

His eagerness for creating continued into building model airplanes and aerospace science fair projects in high school. “I began developing an interest in aircraft and the space program,” he said.

Southbound

Tired of New York winters, Roach enrolled at Georgia Tech, attracted by its aerospace engineering work-study co-op program, which alternated semesters of learning with applying engineering principles. It didn’t hurt that these jobs also helped him pay his tuition. “The co-op program took five years to complete, but the experience was invaluable,” he said. “I worked at the Naval Air Facility, Boeing Aerospace, and later at the Johnson Space Center, while earning an advanced degree at the University of Texas.”

At Boeing, Roach analyzed and solved hardware issues for aircraft coming through the assembly line: if there was a problem, he and his crew got the call. At Johnson Space Center, his work focused on finite element modeling, primarily for spacecraft payloads.

He also spent a summer between undergraduate and graduate school at the National Aerospace Lab in the Netherlands, conducting modeling analyses and experimental work as part of a research assistantship. “That job was another formative experience for me,” Roach said. “It allowed me to work with people from a different country, take some risks, try new things, and be independent in research and development.”

Landing at Sandia

As he approached graduation, Sandia Labs was actively recruiting at the University of Texas with a compelling pitch.

“I wanted to do something more general coming out of school,” Roach said. “The size and structure of Sandia seemed right. There was the diversity of programs, allowing me to move within the Labs — like going to a different company without actually moving, which was very attractive to me.”

Although he had decided against going into aviation after graduating, it was serendipitous that he landed right back in the aircraft industry as part of Sandia’s new AANC. In the early stages, the center consisted of Roach and his manager, Pat Walter, but they had access to allied expertise at the Labs.

“One of the appealing aspects of this program was the ‘work-for-others’ design, demonstrating that Sandia Labs was a national resource for addressing a wide array of engineering challenges,” Roach said. “We used our expertise across the board, and showed time and again that we could assemble the right team to achieve our goals.”

The program was also driven by the 1988 Aloha accident, a flight between Hilo and Honolulu, during which the upper portion of the forward fuselage broke free at 24,000 feet. Miraculously, but tragically, only a flight attendant perished.

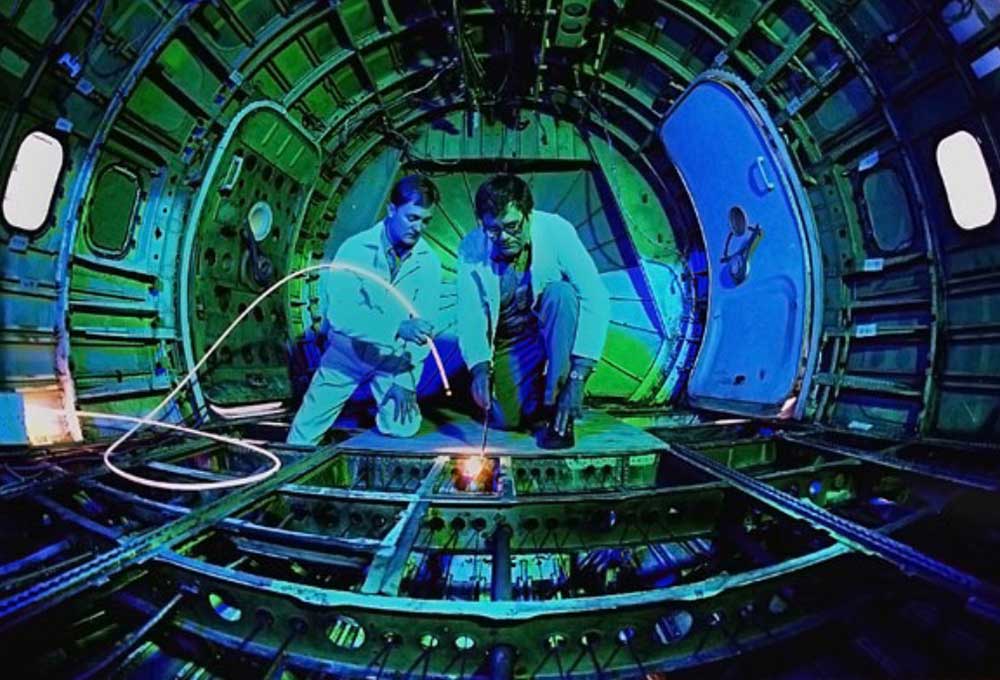

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board’s investigation concluded that the accident was caused by metal fatigue exacerbated by crevice corrosion. “We began researching widespread fatigue damage and small crack detection in aircraft,” Roach said, “leading to several programs that advanced nondestructive inspection principles, or NDI, to improve damage detection during aircraft maintenance.”

Roach, with support from matrixed Sandia experts, began statistically establishing NDI performance standards. “There are two sides to the equation,” he said. “There’s the damage tolerance analysis, which assesses how much damage an aircraft can withstand and still operate safely, and then there’s the NDI performance, which established how small of a flaw can be detected. If the damage tolerance determines an aircraft can withstand a 0.1-inch crack, but an inspector cannot find a crack until it’s 0.25-inch long, there’s a problem. We ensured the statistical performance of aging materials was compatible with the probability of detection.”

Next, Roach and the team evaluated aircraft maintenance inspectors in the field and their performance with different pieces of detection equipment. This led to human-factor studies and procedural changes, resulting in improved aircraft maintenance work.

Eventually, the work expanded to include electrical systems, advanced materials, propulsion systems, landing gear, aircraft certification, regulatory measures and more. Basically, the team covered all aspects of airworthiness assurance.

Be the change

“One of the things I really liked about the center was that we worked across the industry,” Roach said. “For most of our projects, our teams included airlines and aircraft manufacturers from around the world — Boeing, Airbus, Embraer — as well as maintenance and repair organizations, universities, the FAA and regulators in foreign countries.”

Roach spoke proudly of the program’s numerous accomplishments, many of which revolutionized the aircraft industry.

“We created and managed hundreds of programs,” he said. “One was an advanced repair method using bonding composite or laminates on aircraft, rather than riveted metallic-patch repairs, which can create extra holes and crack-initiation sites. Bonding offers better load transfer, and composites don’t corrode. Ultimately, we got it introduced into the Boeing manuals.”

The center also introduced onboard sensors to create a smart aircraft that automatically alerts maintenance personnel where an aircraft needs attention, whether structural or mechanical. And the center was called upon by NASA to help develop an inspection method to ensure the integrity of heat shields prior to each mission following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. “Many of our concepts and technologies were adopted by the mining, wind energy and automotive industries as well,” Roach said.

As the aviation industry moved to embrace composite materials in aircraft manufacturing, so did AANC. In the early 2000s, the center began analyzing manufacturing processes and studying problems with weak bonds. What’s the impact effect of a hailstorm, or ground equipment if driven into the side of the aircraft? What are the deteriorating effects of porosity when a part is made? These progressive programs enabled the center to maintain its relevancy and longevity.

Eastbound

In 2021, the center was brought in-house by the Federal Aviation Administration Tech Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey, after a 30-year run at Sandia. Roach saw it coming with changes in focus and funding.

“I wanted to see the center gracefully handed off, and we had it in a position where it could be operated elsewhere,” he said. “We loaded up four transporters of assets, shipped them out and closed the hangar facility.”

Looking back, the secrets to success became very clear to Roach. Search out and immerse yourself in important work you love and surround yourself with people smarter than you. “In my 35-plus years at Sandia, I was very blessed to have achieved both,” he said.

“I’m very grateful to have been part of the airworthiness assurance program,” he added. “We had extraordinarily detailed teams that left no stone unturned. It was important, challenging work filled with innovative thinkers.”

Roach remains active in airworthiness assurance, enjoying part-time consulting work and keeping in touch with his engineering colleagues around the world.

Spin-offs, investigations and innovation

By Kristen Meub

Some projects of note, including spin-off programs for other industries, include:

Accident investigations: The center supported accident investigations for TWA800, Swiss Air111, American Airline587 and several rotorcraft accidents. All programs resulted in the introduction of enhanced inspection methods for critical components.

Space shuttle program: After the space shuttle Columbia accident, the center worked on NASA’s Return to Flight program to develop an inspection system to certify each space shuttle before launch.

Syncrude Canada and Exxon Mobil oil exploration: Composite expertise gained from aviation programs was used to produce new repair methods for high-cycle oil recovery equipment.

Monitoring bridge health: Expertise from the center’s airplane safety research was applied to monitor the health of bridges.

Robotic inspection of wind blades: The center’s expertise in nondestructive inspection was applied to develop a robotic inspection system to monitor the integrity of the blades on wind turbines.

Aircraft designs for tomorrow: In its work to deploy advanced aircraft maintenance technology and new materials, the Airworthiness Assurance Center teamed with more than 300 companies and government organizations and conducted strategic partnership projects in 10 countries.