5,000 Sandia employees worked to qualify bomb

Sandia marked a major milestone when the nuclear security enterprise successfully produced the first completely refurbished bomb for the B61-12 Life Extension Program in November 2021.

“This is the first complete unit built with nuclear and non-nuclear components that has been fully qualified from the ground up,” said David Wiegandt, a Sandia senior manager on the B61-12 program. “The first production unit is the first war reserve B61-12 built at Pantex that meets all customer requirements and is acceptable for use by the U.S. Air Force.”

More than 5,000 employees have worked on the B61-12 program at Sandia during the last decade.

“Sandia’s role within the complex is unique,” said Jim Handrock, Sandia Weapons Systems Engineering director. “We have the design engineering responsibility for the non-nuclear components, and also the key systems integration role to put all the individual parts together to make sure that everything does what needs to be done to provide the full system to the customer.”

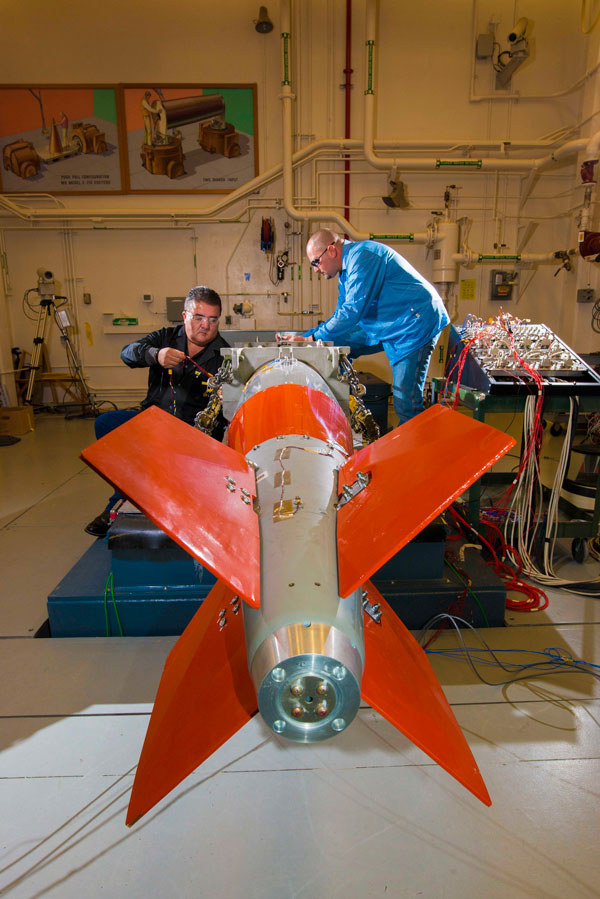

As part of the program, Sandia worked to refurbish, replace or reuse about 50 different components and subsystems that make up the B61-12.

“In addition to design development, we completed the highly rigorous qualification, verification and validation testing to demonstrate that the B61-12 will always work with high reliability when authorized and never function under any other conditions,” David said.

The B61, a nuclear gravity bomb deployed from Air Force and North Atlantic Treaty Organization bases, has been in service since 1968. The B61-12 will replace most older modifications of the B61 and have an extended service life of at least 20 years. The life extension program addresses all known age-related concerns found within the nation’s stockpile of B61 weapons, upgrades encryption algorithms, modernizes the safety and use-control features of the weapon and supports compatibility with future aircraft designs.

Sandia, Los Alamos National Laboratory and Boeing are the design agencies responsible for the design and engineering of the B61-12, with Sandia also producing custom electronics. Additional production activities are performed at Kansas City National Security Campus, Y-12 National Security Complex, the Savannah River Site and the Pantex Plant.

The refurbished B61-12 is set to begin full-scale production in May, with completion expected in 2026.

Design, testing and aircraft compatibility

The program began with a concept phase in which the team developed various weapon architectures that would meet NNSA and Air Force requirements. After the design was stabilized, the team started to develop and produce the individual components that go into the weapon, then spent several years integrating those components into systems, and then tested them and made modifications and refinements as necessary. After about three design cycles, the team reached the final design, Matt Kerschen, a Sandia manager on the B61-12, said.

Matt described a couple firsts for the program, including integrating an Air Force supplied tailkit assembly that guides the bomb to its target location and implementing a new digital interface between the bomb and the aircraft flying it.

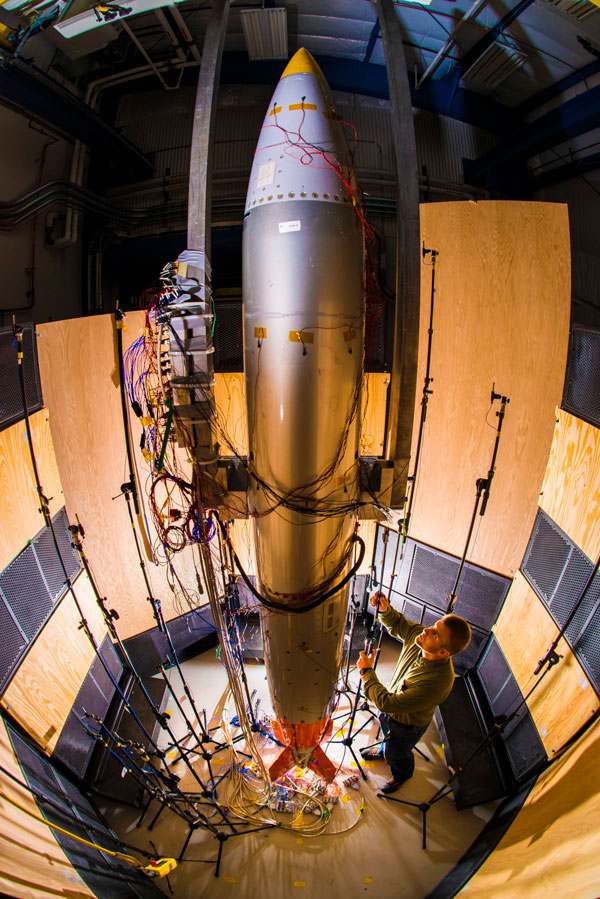

Another key part of the program was the development and qualification testing of the bomb. Sandia completed a series of tests determining how the refurbished B61-12 would handle temperature, shock, vibration, radiation, humidity and more throughout its extended lifetime.

“We spent multiple years qualifying the design by running a series of laboratory and ground tests where we built up full-scale mock bombs and subjected them to a lifetime of environments and then subsequently functioned in them,” Matt said.

Sandia also coordinated with the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center to test compatibility between the B61-12 and the different aircrafts that will be capable of deploying it, Rich Otten, a Sandia senior manager on the B61-12, said.

“It starts with on-the-ground evaluations of the electrical system to ensure the B61-12 communicates with the aircraft and usually concludes with a flight test at Tonopah Test Range,” Rich said. “We learn a lot from both flight and ground tests. We want to make sure we understand everything before we fly, and a flight test is a final proof that in the combined environments the B61-12 operates as expected.”

Exceptional service in the national interest

Jim, who has led the B61-12 program at Sandia for 11 years, said the scope of the program presented challenges and opportunities that helped the Labs rejuvenate its weapons modernization capabilities.

“Sandia hadn’t had this level of work in a modernization program for two decades, so there was a lot of work to relearn and reconstitute this capability,” Jim said. “We instituted earned-value management at a level that had never been done before on a nuclear weapons system, we built up an assembly operation the lab hadn’t seen in decades and set up environmental testing facilities important for the success of the program.”

Jim said participation in successful flight and lab tests were great growth opportunities for staff in terms of learning how to realize weapons systems, and that the commitment of the staff was critical to the success of the program.

“For a lot of people, it’s been a significant commitment, both professionally and personally, to be able to get this work done in the timeframe and manner that the nation needs. Everybody who has worked on this program is to be commended for the efforts, contributions and sacrifices they’ve made to make it successful.”

Matt has worked on the B61-12 at Sandia since the program began. He said he has stayed on the program because he believes the work is important for the security of the nation and the engineering challenges have been exciting to solve.

“It’s been a once-in-a-career type of experience,” Matt said. “When you can take a concept for a weapon that you developed on paper and presentation slides, and then be able to turn that into actual hardware that functions as designed, that’s really rewarding.”

Matt recalled the first end-to-end laboratory test and the first flight during the program as being big accomplishments on the way to the first production unit milestone.

“We worked together for years wringing out all of the bugs in the system in the lab before we got to that first flight test off of an F-15E,” Matt said. “There was a huge sense of accomplishment for the entire team to see everything we’ve worked on finally come together and function as designed. There’s been a lot of examples like that on the program, where the team is working to accomplish a major milestone for a long period of time and then that tremendous sense of accomplishment when you finally get there.”

For David, working on the B61 runs in the family. His father, Karl Wiegandt, started working at Sandia in 1968 and supported B61 modifications — believed to be B61-1 — as his first program out of school. He performed mechanical drafting for flight test sensing and the handling equipment, or H-Gear, before moving to another weapon system.

“There’s something really special about this program, the people, the morale and the legacy,” David said. “It has really solid team members who believe in how to do sound engineering and really bring the future of safety and security into modern nuclear weapons. That culture is infectious and has drawn a lot of people to it.”

Rich said he’s proud of the work the team, current and past members, has done to achieve this milestone and modernize the B61 for the nation.

“This is a critical element of the nation’s nuclear deterrent, and I’m proud to be part of the team delivering on the common goal of completing the first production unit,” Rich said. “This is not an end; it’s the beginning of production. We’ve designed, tested and proved this completely refurbished B61, and now it’s ready for the transition to full-scale production.”