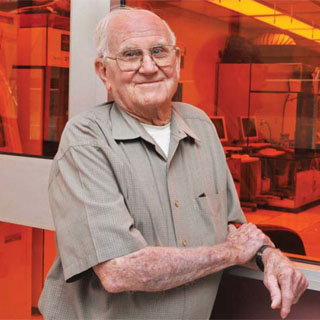

Cleanroom inventor Willis Whitfield, who passed away this week at age 92, lived long enough to see his creation mark its 50th anniversary. Willis, who retired from Sandia in 1984, pauses here during a tour of a cleanroom in Sandia’s microsystems fabrication facility. (Photo by Randy Montoya)

When Willis Whitfield invented the laminar-flow cleanroom 50 years ago, researchers and industrialists didn’t believe it at first. But within a few short years, $50 billion worth of laminar-flow cleanrooms were being built worldwide and the invention is still in use today.

The retired Sandia physicist, dubbed “Mr. Clean” by TIME Magazine at the time, passed away this week at age 92.

The travel, scientific presentations, and accolades didn’t change the unassuming scientist, who was always modest about the invention that revolutionized manufacturing in electronics and pharmaceuticals, made hospital operating rooms safer, and helped further space exploration.

Sandia President and Labs Director Paul Hommert remembered Willis as a Sandia pioneer.

“He represented the very best of Sandia,” Paul says. “An exemplary researcher, a physicist who became an engineer’s engineer, Willis lived in that sweet spot where the best technical work is always done, at the intersection of skill, experience, training, and intuition. His breakthrough concept for a new kind of clean room, orders of magnitude more effective than anything else available in the early 1960s, came at just the right time to usher in a new era of electronics, health care, scientific research, and space exploration. His impact was immense; even immeasurable. We are proud to have called him a fellow Sandian, and we join with his family to mourn his passing.”

Willis, the son of Texas cotton farmers who learned to do for themselves by fixing their own equipment, was in the Navy working on radar and then worked with rocket propellants out East before coming to work at Sandia, his son, Jim Whitfield, says. By the time he came to Sandia in 1954, his motivation set the stage for the invention because he felt like he was behind his co-workers and needed to do something catch up, he says.

In 1959, Willis was asked to solve a manufacturing problem for Sandia, so he invented the laminar-flow cleanroom, which, with slight modifications, is the industry standard today.

“He built it, found out no one had done it that way before, and said, ‘I don’t understand why [no one had invented it]. It’s so simple,’” recalls Jim Whitfield, who was a young child at the time. “I heard someone ask him how long did it take him to think of that idea and he said, ‘Five minutes; I just did the obvious thing.’”

Shortly after the invention was publicized, Jim Whitfield recalls his father coming home and telling his mother he got a “raisin.”

Puzzled about her joyful reaction about a food found in the family pantry, the boy then saw his dad’s appearance on a television news program and “at that point, I knew something was very different about that raisin.”

But a higher salary was a small part of the story. Jim Whitfield recalls practically living in airports while he father flew all over the country presenting his inventions at conferences and to companies that wanted to use the technology.

Solving a problem

In 1959, nuclear weapons components — mainly mechanical switching parts — were becoming smaller and microscopic dust particles were preventing manufacturers from achieving the quality Sandia needed, so Willis’ supervisors asked his group to find a solution, Sandia historian Rebecca Ullrich (9532) says.

While Willis might have come up with the idea quickly, months of research and talking with people led up to that moment of discovery, Rebecca says.

Willis discovered the practice at the time was to tightly seal cleanrooms, wear protective clothing, and vacuum often. Still, the airflow was turbulent in existing cleanrooms and particles introduced were not removed. These measures didn’t create the necessary conditions for close-tolerance manufacturing, she says.

Rebecca says Willis looked at blowers, vents, grading, and the cost per square foot to build his invention, so that it would be something people could afford.

By the end of 1960, Willis had his initial drawings for a 10-by-6 cleanroom. His solution was to constantly flush out the room with highly filtered air. In that first model, Willis designed a workbench along one wall. Clean air entered the room from a bank of filters that were 99.97 percent efficient in removing particles larger than 0.3 microns. For example, cigarette smoke blown in one side comes out the other as clean air, according to a 1962 Lab News article.

The air was circulated in the room at a rate of 4,000 cubic feet or about 10 changes of air per minute, an amount of air movement barely perceptible to the workers inside. The linear speed of air was slightly more than 1 mph, about the same as that felt walking through a still room, according to the article.

In a later modification, the air was passed down over the work area instead of across, getting an assist from gravity in carrying troublesome particles into the floor, which was covered with grating. Filters underneath cleaned the air and it was circulated back around to re-enter the room. The constant flow of clean air performed a sweeping function.

When the first cleanroom was tested “the dust counters went to nearly zero. We thought they were broken,” Willis said in a 1993 videotaped interview.

The laminar-flow cleanroom created a work environment that was more than 1,000 times cleaner than the cleanrooms that were in use at the time.

According to tests at the time, the laminar-flow cleanroom’s work area contained an average of 750 dust particles one-third of a micron in size or larger per cubic foot of air. (A micron is equal to 40-millionths of an inch.) That’s compared to average dust counts of more than 1 million particles per cubic foot of air in one of the best conventional cleanrooms in use at the time.

Bringing the cleanroom to the world

Willis gave his initial paper at the Institute of Environmental Sciences meeting in Chicago in 1962.

“While he’s in Chicago the TIME article hits and his phone just does not stop ringing,” Rebecca says. “Industry jumped all over it.”

But at a standing-room-only talk about a year later at the American Society for Contamination Control in Boston, manufacturers challenged the invention’s claims, accusing Willis of perpetuating a hoax, Rebecca says.

Jim Whitfield remembers his father’s story: “The numbers he was showing were unbelievable. At this conference, people were telling him that can’t be right. Then one of his colleagues [from Bell Labs] got up and said he thought Whitfield was wrong. His numbers are 10 times too conservative. So, he knew at that point that it was a dramatic shift in the technology.”

Others recognized it too.

Within a couple years, $50 billion worth of cleanrooms had been built worldwide.

‘They come to you’

“When you have something that everyone wants, they come to you,” Willis said in the videotaped interview. “The desperate need for this accelerated the gap between development and production drastically.”

RCA and General Motors were early adopters of the cleanroom and the invention revolutionized the pharmaceuticals and microelectronics industries, Rebecca says.

MD Anderson Hospital in Houston built 22 cleanrooms to prevent infections in leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy, Willis said in the 1993 interview. And Bataan Memorial Hospital, which later became Lovelace Hospital, was the first hospital to use laminar-flow cleanrooms in their operating rooms to prevent infections, Rebecca says.

‘He would always do the right thing’

Willis eventually worked with NASA to provide planetary quarantine efforts during missions to the moon and Mars and spacecraft sterilization techniques, Rebecca says.

But fame did not change Willis.

“He was a nice guy, very honest, very straightforward,” Rebecca says. “He was very modest about it. His values meant he would always do the right thing, even if it cost him personally. He made sure other people shared credit for things.”

The cleanroom design also made it possible to standardize cleanrooms for the first time, and a group of Sandia employees contributed to establishing federal standards for the government in 1963.

Had he invented the cleanroom today, Willis Whitfield might have become a very wealthy man. But back in the 1960s, the predecessor to DOE, the Atomic Energy Commission, held the patent in the public domain, Rebecca says.

During his career, Willis accrued many awards and honors, including the Holley Medal, presented by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Other recipients of the medal have included Henry Ford, Edwin Land (for the Polaroid Land Camera), William Shockley (for the invention of the transistor), Elmer Sperry (for the gyrocompass), and many others

After his retirement from Sandia in 1984, Willis continued to consult with all who would call him. He remained active in the Hoffmantown Baptist Church in Albuquerque, where he served in many capacities.

Willis is survived by his wife, Belva; son Joe Ray and wife, Joy, of Portland, Ore.; son James Donald of Albuquerque; a brother, Lawrence Whitfield; and sister, Amy Blackburn, both from Dallas, Texas.

Willis Whitfield lived to see his invention turn 50 this year, but was unable to give one last interview, so his son spoke for him, saying, “I’m sure in his heart, he was very satisfied that he made such a big and positive impact on society.”