As Justin Olmstead wrote in the introduction to last year’s “From Nuclear Weapons to Global Security: 75 Years of Research and Development at Sandia National Laboratories,” “Sandia’s success is a result of the people who work at the Labs.” Considering the types of complex problems Sandia has been charged to solve over the past 75 years, that success is largely due to the work of people who are, not coincidentally, our nation’s most talented engineers.

But what makes engineering at Sandia particularly special is not just the sheer number of engineers on staff — although that number is impressive, comprising about half the Labs — but the variety of engineering roles filled by people working together across many organizations, bringing their breadth of knowledge and diversity of backgrounds to the work.

One would be forgiven for thinking that Sandia is simply a place for nuclear engineers. While the Labs has people serving in that role, it is also a home for aeronautical, biological sciences, chemical, computer, electrical, electronics, geosciences, mechanical and optical engineers, and more.

In keeping with Sandia’s vision to be the “nation’s premier science and engineering laboratory for national security and technology innovation,” it recruits the best engineers to support its mission. In parallel with a new video for Engineers Week 2025, four of these engineers sat down with Lab News to provide insight into why their work matters, what challenges them and why they choose to practice their chosen discipline at Sandia.

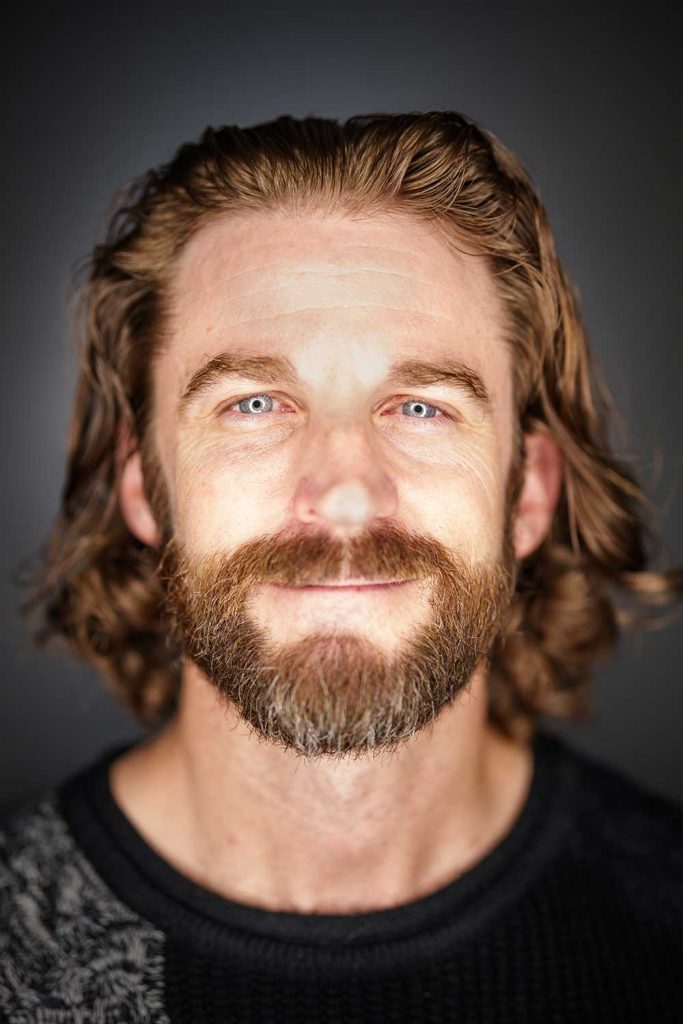

Aaron Murray, electrical engineer

At an institution that has been operating for over 75 years, pursuing work at Sandia can feel like entering the family business. Aaron Murray’s tie to the Labs was his grandfather, who worked at Sandia before Aaron was even born. “He would share countless stories about the incredible work being done here,” Aaron said. “He often spoke of the travel opportunities and the significant impact his efforts had on our great nation.”

Aaron dreamed of being an astronaut. “I would gaze up at the night sky, filled with wonder about the existence of life and the possibilities of new promising futures,” he said. That quest for fulfilling a promising future led him to a degree in electrical engineering and eventually to his current role where he supports nuclear weapon qualification and continues to learn and grow every day.

“Many of the challenges I encounter at Sandia arise from fully grasping the complexities of a problem. It can be tempting to leap directly to a solution without carefully considering options and trade-offs. This tendency often results in inefficiencies and typically yields a less optimal final outcome.”

His positive attitude is infectious and has played a major part in his success. “I like to believe the impossible is possible, which seems to enable and allow for a wide-open solution space that would have been completely crushed with believing something can’t be done,” Aaron said. “It’s amazing how almost getting there solves more problems that people think. This philosophy is something I learned to embrace, and I wish I had embraced it much sooner in my career.”

And he still hasn’t given up on his dream of journeying into space. “I will strive to achieve this goal for as long as I live for a glimpse into the extraordinary experience of being an astronaut.”

Kelsey Carilli, systems engineer, Virtual Technologies and Engineering

Like Aaron, a younger Kelsey Carilli dreamed of being an astronaut…and an inventor … and a veterinarian.

“I had amazing math and science teachers who helped me discover my passion for math and physics,” she said. “During undergrad, I took an intro to materials science course and fell in love with the hands-on lab work and the discovery and investigation process.” That experience led her down a path toward a master’s degree in materials science and engineering from New Mexico Tech and an internship at Sandia. “The need to understand how materials impact other disciplines helped plant the seeds for my interests in overall integration, leading me to systems engineering,” she said.

Originally, working at Sandia just made practical sense — her interests aligned well with the innovations being made at the Labs. Over time though, she made an emotional connection to Sandia as well.

When asked what she finds challenging at work, Kelsey highlighted the opportunities and obstacles in communicating with a broad and diverse group of coworkers. “One of my mentors with decades at Sandia put it nicely: in order to be a successful communicator, you have to extend your vocabulary and understanding to the other person’s world view.” A major lesson Kelsey has learned over her Sandia career is to “identify opportunities early on to understand the background, interests and motivators of collaborators.”

And like everybody at Sandia, her contributions are changing the world in ways both big and small. “I believe my boots-on-the-ground-level contributions are feeding into the overall success of the digital engineering transformation at Sandia, which feeds into the higher mission objectives for nuclear deterrence,” she said.

From a more personal perspective, her biggest source of pride at Sandia has been mentoring students and early career staff. “Due to the multigenerational nature of the work conducted at Sandia,” Kelsey said, “the investment in the next generation will result in long-term positive change.”

One of her proudest moments was sharing her experiences with an intern and watching their growth into a staff member. “Transferring my technical and professional maturation experience and watching that manifest in others has been so rewarding,” she said.

“I like to think the small impacts I have on their outlook will have a big impact on the work we do at Sandia.”

Justin Wilgus, geosciences engineer

When Justin Wilgus was very young, he wanted to be a truck driver, seeing America from behind the dash of a big rig pointed down the open highway. As he got older, he found fulfillment in building things and began working in the construction industry. But after taking a few college courses, he pursued a long-held interest in geology in earnest, earning a doctorate in earth and planetary science with a focus in seismology.

Above all, Justin wanted to do work that made a difference, and he found that work at Sandia, now assessing the performance of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.

WIPP is “one of the only operational deep geologic nuclear waste repositories in the world,” Justin said, and in his role he serves “the people of New Mexico, the nation and the world through responsible environmental stewardship.” It’s an important position with far-reaching implications.

“I get to work with multiple physical process models that range in disciplines from actinide chemistry to hydrogeology,” Justin said. “I find the interdisciplinary nature of the work fascinating, but the complexity and diversity of the work can be challenging, especially as it pertains to understanding interactions between parts of the system and potential impacts on repository performance.”

WIPP has cleaned up numerous generator sites across the United States as part of its mission to dispose of defense-generated transuranic waste. Its success can be attributed to passionate engineers like Justin who believe in the importance of the mission.

But if he could try one job for just one day, Justin still thinks he would give trucking a go. “Honestly, I still want to get a commercial driver’s license. Maybe I could do some over-the-road trucking in retirement,” Justin said, “if the industry is not entirely automated by then.”

Reflecting on his career thus far, Justin added, “I have come a long way and have a lot to offer. At the same time, I have a ways to go and a lot to learn.”

Kathleen Shurkin, computer science engineer

Kathleen Shurkin dreamed of being a sci-fi writer, creating faraway places and the ways to reach them. She pursued a degree in astrophysics with the intention of incorporating accurate physics principles into her writing — and in doing so she found out that the research itself was pretty fun too.

After receiving a Master of Science in physics from Heidelberg University in Germany, she took her expertise to the Air Force Research Laboratory, where her passion shifted again. With a strong interest in software development, Kathleen came to Sandia, where she now works in Integrated Software Solutions.

A throughline in Kathleen’s career has been her pursuit of challenges, and she noted that the challenges in her line of work are also what make it extremely rewarding. “The biggest challenge is consistently being innovative,” Kathleen said. “We are often tasked to solve problems that have never been solved before, which is incredibly exciting but can also be overwhelming at times.”

Making the impossible possible is no small task, whether writing chapters or code.

When asked how she is “changing the world” through her work at Sandia, Kathleen focused on the little things that make big things possible: “I believe that small actions can have the biggest impacts, so I would say that the most impactful way that I am changing the world is by creating positive connections with others” she said, adding, “No one changes the world in isolation.”

And although her work is firmly rooted on earth, she is still looking toward the sky for inspiration. “My top bucket list item is to see the aurora borealis in-person,” she said. “Preferably while staying at one of the glass igloo resorts in Finland.”