A 6-year project that turned into 25

In 1975, the nation asked Sandia to investigate the possibility of building a repository in New Mexico for the disposal of radioactive transuranic defense waste. Little did those assigned to the project know that the task would absorb most of their careers and become one of the most controversial and important projects in U.S. history.

The purpose

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, or WIPP, was created at the direction of the federal government. The necessity for a repository grew with nuclear research, nuclear power production and the nuclear defense program that began with the Manhattan Project. While nuclear waste was piling up during the Cold War, no solution to safely storing and disposing of it had been found. In Los Alamos, radioactive and toxic materials were dumped into canyons, according to a DOE report: Closing the Circle: The Department of Energy and Environmental Management 1942-1994. Sandia needed to do something no one else had managed to do before. To this day, WIPP is the only U.S. deep geologic repository for the disposal of defense-related transuranic waste.

A monumental task

“We were, in retrospect, a small, somewhat naive group of Sandians that first began work on the WIPP project in 1975,” remembers Wendell Weart, known as the “Sultan of Salt” for his contributions to the project. “I was involved in WIPP for at least 30 years. I think everyone from Sandia who worked on the project felt like it was the thing to do for the nation.”

Sandia’s team started with about a dozen people but over the years grew to nearly 170. Weart, who died on Sept. 26, worked longer on the project than anyone else. In a phone interview last year, he spoke passionately about what it took to get WIPP open.

“It’s something that took a very dedicated team of Sandians working much longer than they expected. Working on WIPP is not a one-person effort; it takes a team, and I had that team,” Weart said.

Site challenges

Sandia inherited the WIPP project and a proposed site from Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The site was the pure salt of the Salado Formation in the Los Medanos area, about 25 miles east of Carlsbad, New Mexico. While the plan was to bury the waste 1,500 to 3,000 feet deep, it didn’t take the Sandia team long to determine that the site was geologically unsuitable. After drilling the first borehole in 1975, the Sandia team discovered unexpected geology: steeply dipping salt beds and brine that presented serious obstacles.

That drilling almost turned deadly. Brine, containing a heavy concentration of hydrogen sulfide, came gushing out of a borehole. Sandian Tom Lawes, who was working nearby, inhaled the gas. There was no medical oxygen on-site but Lawes had the shrewdness to direct his coworkers to the welding truck where oxygen was stored, ultimately saving his own life.

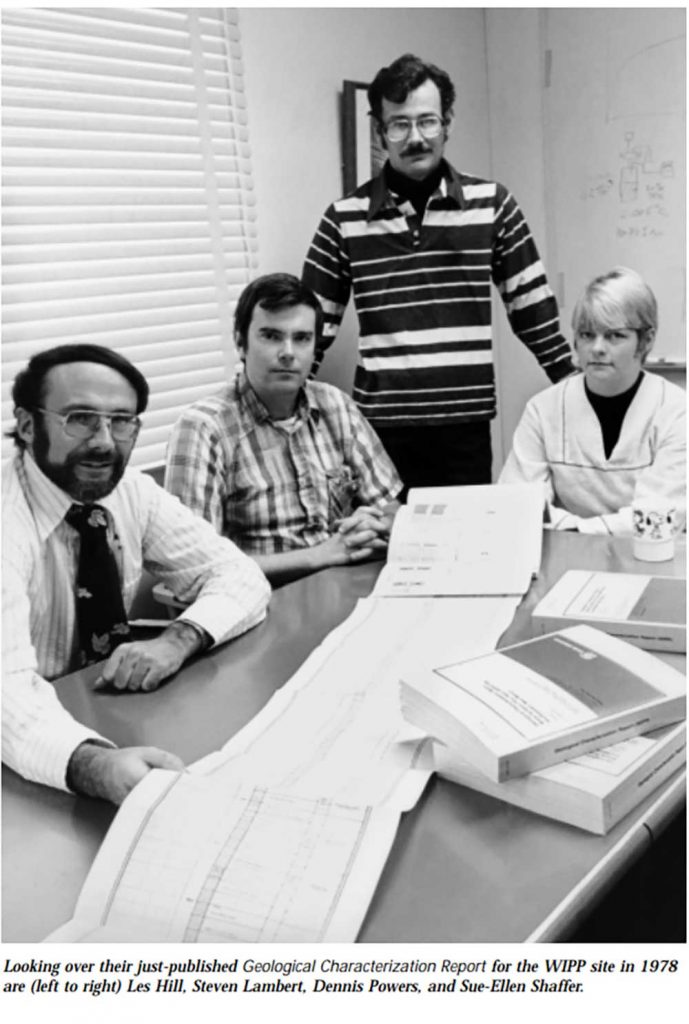

The team decided it had to start from scratch and search for a new site. This would be one of the biggest challenges for the Sandia team, led by supervisor Les Hill and geologist Dennis Powers. From that point, the team grew rapidly. After more than a year of investigation, research and exploration, the team settled on a new site seven miles from the original — in the center of the Delaware Basin.

Facility design and environmental impacts

After abandoning the first site, the team also had to abandon the initial facility design and start over. This effort, led by Leo Scully, would prove challenging and time-consuming. Simultaneously, a group led by Sandian Mel Merritt studied the site’s environmental impact.

It was not an easy task, Weart said. “They had to be able to show that this facility would be safe and protect the waste for 10,000 years. The way to approach that was through calculation.”

The team released its new conceptual design in 1979 and its environmental impact statement in October 1980.

Political challenges

With the project came much opposition. Not only did they have to convince the government WIPP was safe, but they also had to convince the American people. The community of Carlsbad was mostly supportive, eager to secure jobs to replace the waning potash industry. However, the idea of storing nuclear waste triggered opposition in New Mexico and elsewhere. About 1,500 people showed up for three days of DOE public meetings in April 1978 in Carlsbad, Albuquerque and Santa Fe — some to learn more, others to share their fears. Subsequent meetings over the next decade also drew crowds.

The concerns raised publicly by politicians in Washington, D.C., and New Mexico failed to reassure Americans. In 1980, President Carter signed a bill authorizing the construction of WIPP but made it clear he was not endorsing this approach to nuclear waste disposal. That bill quickly was met by a lawsuit from New Mexico Attorney General Jeff Bingaman, who asked a district court to halt work on WIPP to “vindicate rights guaranteed to the state of New Mexico.” The state was fighting for a voice in what would happen at WIPP, even though it was a federal project. The fight dragged on for many years, as did other fights over what type of waste should be stored at WIPP, how it should be regulated and whether it should be drilled at all.

During this time, there were repeated changes in those overseeing the project, and with each new face, there was a new perspective as to what WIPP should look like and what its purpose should be. Despite the decades-long yo-yo effect, the Sandia team remained determined to see it through.

Construction

In September 1981, the team began drilling the first two shafts at WIPP for research and testing. That decision was not welcomed by some.

“With tombstones and picket signs, dozens of people demonstrated at the Albuquerque WIPP headquarters. Twenty-one activists and eight media representatives were arrested when they attempted to enter the buffer zone near the site,” the Albuquerque Journal reported.

It would be another two years before the political unrest would ease and DOE officially approved full construction. It was then, in September 1983, that DOE invited the media to visit the site.

Eric McCrossen, an editorial writer for the Albuquerque Journal, described his experience: “Once you have toured the Waste Isolation Pilot Project under construction, it is difficult to understand the controversy that has surrounded it and it is easier to believe the support the project appears to have from area residents.”

The home stretch

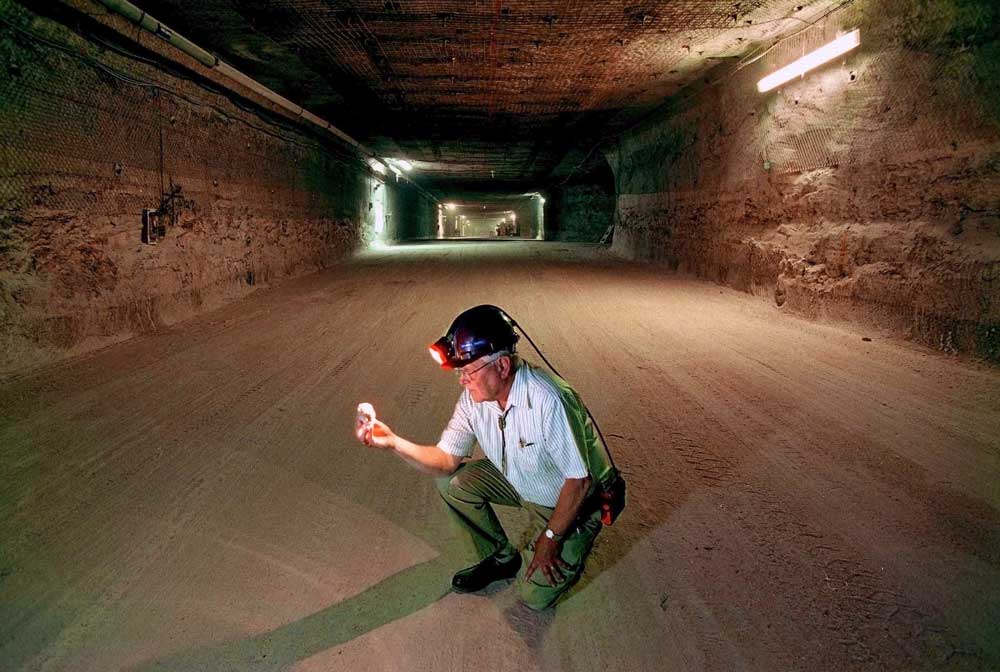

By 1984, enough of the site was complete to begin underground experiments to test the potential environmental effects of the waste repository.

“We had long been doing laboratory experiments to understand the nature of the facility, but we also had to be in the site to test how the salt rock would interact with the waste. That continued for a long time,” Weart said.

This testing was required to satisfy requirements from the Environmental Protection Agency, the designated regulator of WIPP.

During that time, Sandia environmental testing crews conducted experiments to help perfect the TRUPACT-II containers in which transuranic waste was to be transported. Each weighed 12,750 pounds empty and was designed to carry 14 55-gallon drums. Testing included dropping the containers 30 feet onto a steel plate and puncture bar, burning them in a jet fuel pool fire at 1,424 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes and then submersing them under 50 feet of water.

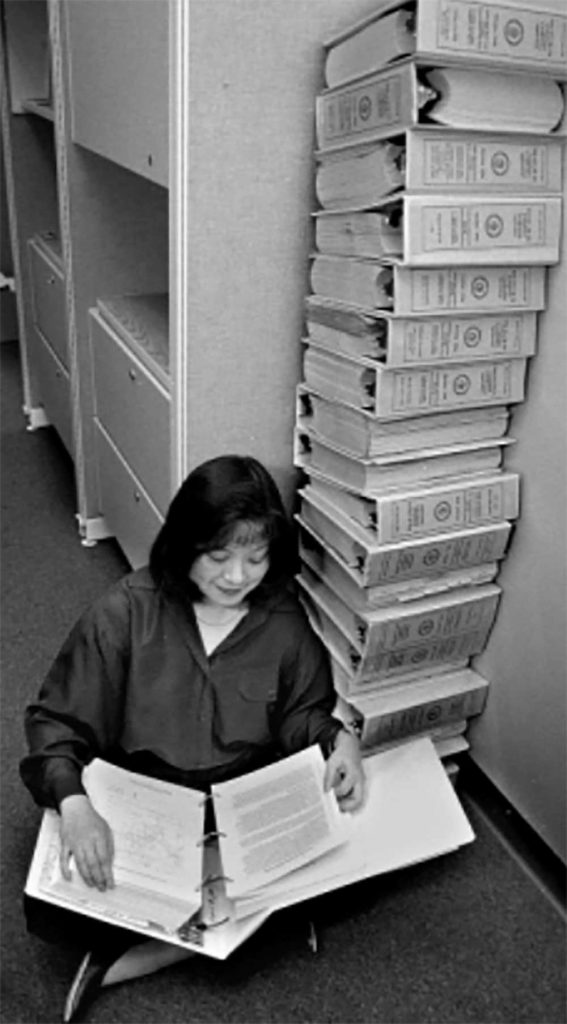

Other Sandia groups were essential players in the lengthy technical efforts required to ensure WIPP’s readiness to accept waste.

In an interview in a 1989 edition of Lab News, around the time that site characterization was completed, Weart expressed confidence that WIPP was safe but recognized the Labs had more to do.

“Proving its safety in quantitative terms would require considerable work for the next few years,” Weart said. A few years turned into nine.

A major milestone came Oct. 20, 1992, when President George W. Bush signed a long-debated bill that transferred the 10,000-acre site permanently from the Department of the Interior to DOE. However, the political debates over WIPP perisisted while Sandia continued its work.

Opening day

Finally, on March 26, 1999, WIPP received its first shipment of transuranic radioactive waste. In the end, the big day wasn’t so big. A single truck carrying transuranic waste arrived at the gates of WIPP without incident after a 342-mile journey from Los Alamos National Laboratory. A few anti-WIPP demonstrators showed up in Los Alamos and Santa Fe, but in Carlsbad, only residents welcomed the shipment. New Mexico Rep. Joe Skeen, a supporter of the WIPP project since its inception, made one of the boldest statements of the day, asking, “God almighty, why did it take so long?”

Since that day, WIPP has received more than 13,000 shipments of waste. WIPP drivers have traveled 17 million miles without a serious accident or injury — equal to 35 round trips to the moon. The original TRUPACT-II containers designed and tested extensively at Sandia are still in use.

A challenging time

Despite its successes, WIPP has experienced setbacks. On Feb. 5, 2014, a salt haul truck caught fire underground. Six workers were treated for smoke inhalation. Nine days later, on Feb. 14, 2014, an air monitor alarm went off, indicating radioactivity in an area near where waste was being stored. These incidents prompted an investigation of safety systems and programs. While it was determined that the radioactivity leak was caused by a drum improperly packed at Los Alamos National Laboratory, the plant shut down for cleaning and improvements, reopening on Jan. 9, 2017.

Looking back

To be part of the building of WIPP is an accomplishment in itself. To work on it for the duration of the project is something entirely different. Wendell Weart is the only person who can claim that distinction. His passion for the project was clear. Even though it brought restless nights and frustrating days, he was proud of what his team accomplished.

“The fact that we succeeded in doing what so many national organizations thought would not be possible showed them that if you are honest with the communities and citizens about what you are doing, you could succeed. WIPP was a beacon to other countries showing that these problems were not without the ability to solve,” Weart said.

Weart also spoke highly of his team that worked year in and year out to make sure WIPP opened its doors. “Sometimes it didn’t feel great because it involved talking with people who didn’t want to hear what you were saying, but in the end, by persistence and by what was clearly dedication from all of our people, I think we were able to convince them it was safe. It’s a good feeling to think you’ve managed this problem successfully.”

Permit renewed

On June 27, WIPP reached another milestone: the New Mexico Environment Department renewed its operating permit for another decade. The permit includes, among other things, a requirement that WIPP prioritize legacy waste cleanup from Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Sandia continues to serve as the science adviser on long-term storage performance at WIPP, with about 50 total Sandia staff there. Lab News published an update on work there two years ago.

Source

Much of the historical information in this story that accompanied the generous descriptions by Wendell Weart came from a Sandia history of WIPP published in 1999: Sandia and the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant 1974-1999, by Carl J. Mora (SAND99-1482).