Sandia’s new testing methods reduce time to test weapons systems

Testing weapons and components in a lab-controlled environment has always been at the center of Sandia’s mission. Since the U.S. stopped underground tests on weapons in the early 1990s, Sandia has developed other methods to conduct experiments that mimic the range of environments a weapons unit might experience. One of the newer methods is getting better results, with fewer tests, in less time.

“Our job in the laboratory is to simulate the environment and lifetime of stress that the weapon units experience out in the field,” said Kevin Cross, a mechanical engineer who oversees Sandia’s vibration lab. “Using multiple input, multiple output testing is a much more realistic representation of what those units experience in flight and out in the field.”

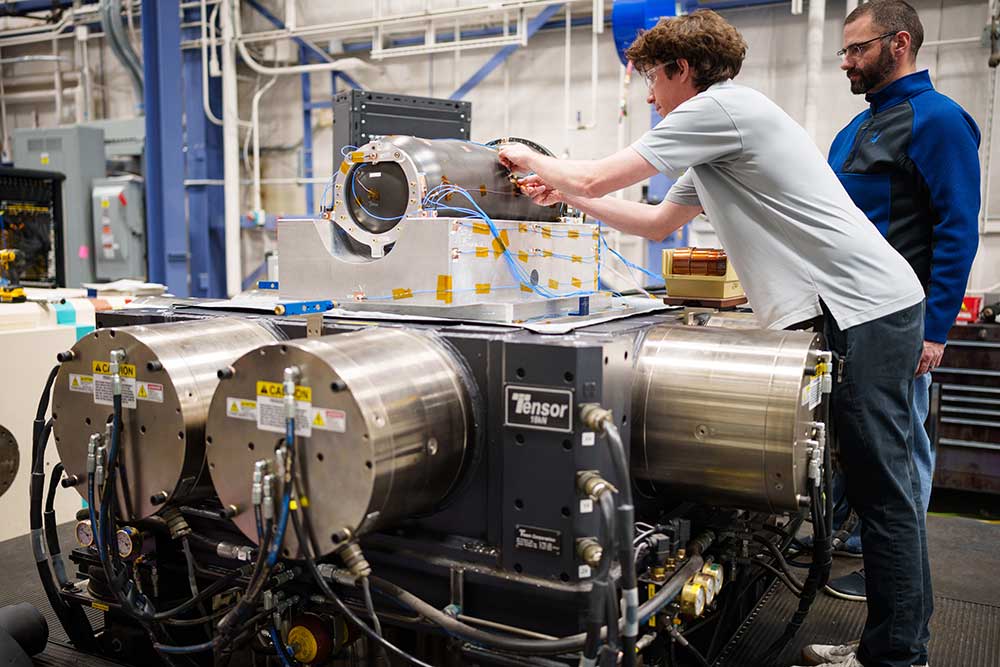

One multiple input, multiple output testing machine is called the six degrees of freedom shaker. The shaker table simultaneously moves the x-, y- and z-axes, while also rotating each axis.

Over the past few years, Sandia has been expanding methodology for multiple input, multiple output experiments for nuclear deterrence systems.

Qualification testing

Sandia recently used the six degrees of freedom shaker for qualification of the W80-4 — a first for a weapons system that will go into the U.S. stockpile. A variety of information is used for qualification — or ensuring the system meets requirements — including experimental data.

“This capability has been beneficial because it more accurately represents the environment a deterrence system would withstand in the field,” said Christy Turner, who oversees system and environmental testing for the W80-4. “It’s also beneficial from a schedule standpoint. Testing using the six degrees of freedom shaker takes about a third of the time as a full mechanical shock and vibration test.”

Sandia has one of only a few six degrees of freedom machines in the country. “In single-axis testing, we test each axis independent of each other, so it’s three times the amount of testing than in a multiple input, multiple output test. We by far lead the way here at Sandia on multiple input, multiple output testing,” Kevin said.

Building techniques and capacity

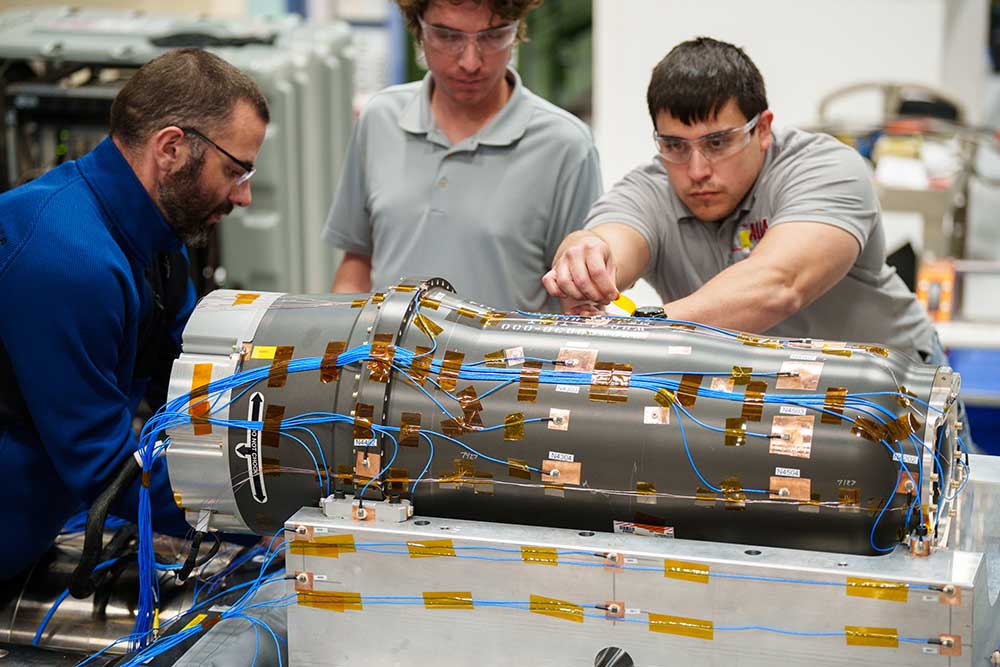

To carry out qualification tests for the W80-4, Kevin and his team developed specific methodology for the system and built a bespoke multiple input, multiple output test stand for it.

“The testing equipment and methodology are building capacity to meet the mission, and it’s giving us higher fidelity data,” Kevin said.

Christy has been pleased with the teamwork. “The experts at the vibration facility have brought us a solution that helps reduce risk from a schedule standpoint. This is an important example of collaboration across divisions at Sandia,” she said.

Since recent environment tests were completed on the W80-4, other nuclear deterrence programs have taken notice and are exploring similar multiple input, multiple output experiments for their systems.

“The big selling point in terms of the nuclear deterrence community is that we can significantly reduce the amount of test time required. Not only are we getting a much better, much more realistic dataset, but we’re also doing it considerably faster,” Kevin said.

Casual conversation sparks transformation

Innovation doesn’t always start in a lab. Pavel Chaplya said the work to use multiple input, multiple output equipment and methods on weapons systems all began a few years ago during a conversation with a Sandia colleague while they were on a business trip. Pavel works on Sandia’s Joint Technology Demonstrator Project. He told his colleague from the vibration lab he needed data about demonstrators, which are full-scale prototypes of weapons technology nonnuclear components.

“We allowed them to put the prototype on the table and shake it. We can accept that risk,” Pavel said.

Ryan Schultz, an environments engineer who works at Sandia’s vibration lab, is one of the employees who worked on the experiments for the Joint Technology Demonstrator Project.

“Having full-system hardware to develop and demonstrate advanced vibration capabilities, without the usual time constraints associated with nuclear deterrence environmental testing, allowed us to focus on our specific technical challenges and have flexibility to try new things,” Ryan said. “Since we had Joint Technology Demonstrator units, we gained experience with full system, nuclear deterrence-like hardware very early on in the development of our tools.”

Those experiments provided data the Joint Technology Demonstrator Project needed. It also helped Delivery Environments, a DOE-funded program, which requires the Labs to demonstrate new capabilities with multiple input, multiple output testing every couple of years. Delivery Environments developed methods and techniques specifically for nuclear deterrence programs.

“The results from the demonstrator hardware got the buy-in of programs of record to use these machines for qualification. It’s a win-win,” Pavel said.

Ryan added that something more important than proving capabilities has resulted from the collaboration. “Having people and processes already in place to support this new technology greatly reduced time, money and risk when doing these environmental tests for nuclear deterrence customers.”