Experimental war gaming provides insightful data for real-world cyberattacks

In Greek mythology, Tantalus so angered Zeus with his treachery that his punishment was to go thirsty and hungry while standing in an always receding pool of water with bountiful fruit trees just above his reach. His fate serves as a reminder to humanity that foolish actions can lead to unpredictable and enduring consequences.

At Sandia, the name Tantalus is associated with an experimental multiplayer online war game used to study different conditions within cyberdeterrence strategy. More importantly, the game is a human research study to gather data about how people’s decisions during threatening situations can impact national security.

“We’re interested in understanding the theory of cyberdeterrence — the notion that the threat of cyberattacks can modify or inhibit the actions of others,” Jon Whetzel, the lead online game designer, said.

To learn more about the human element of cyberdeterrence, researchers pursued increasing Sandia’s experimental war-gaming capabilities, and the Program for Experimental Gaming and Analysis of Strategic Interaction Scenarios created Tantalus. As part of the PEGASIS portfolio, Tantalus was a three-year Laboratory Directed Research and Development project on cyberdeterrence funded through the Energy and Homeland Security Investment Area Team. The project recently ended, and the team published its preliminary findings in September.

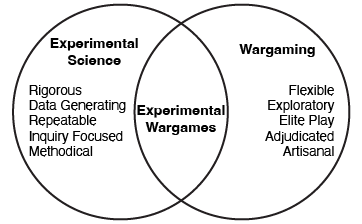

Combining scientific rigor with the art of war game design

Tantalus is unlike most war games because it is experimental instead of experiential — the immersive game differs by overlapping scientific rigor and quantitative assessment methods with the experimental sciences.

“We consider real-world problems,” said systems research analyst Jason Reinhardt. “And the war games are a laboratory where we can experiment on deterrence problems and understand how they change under different circumstances.”

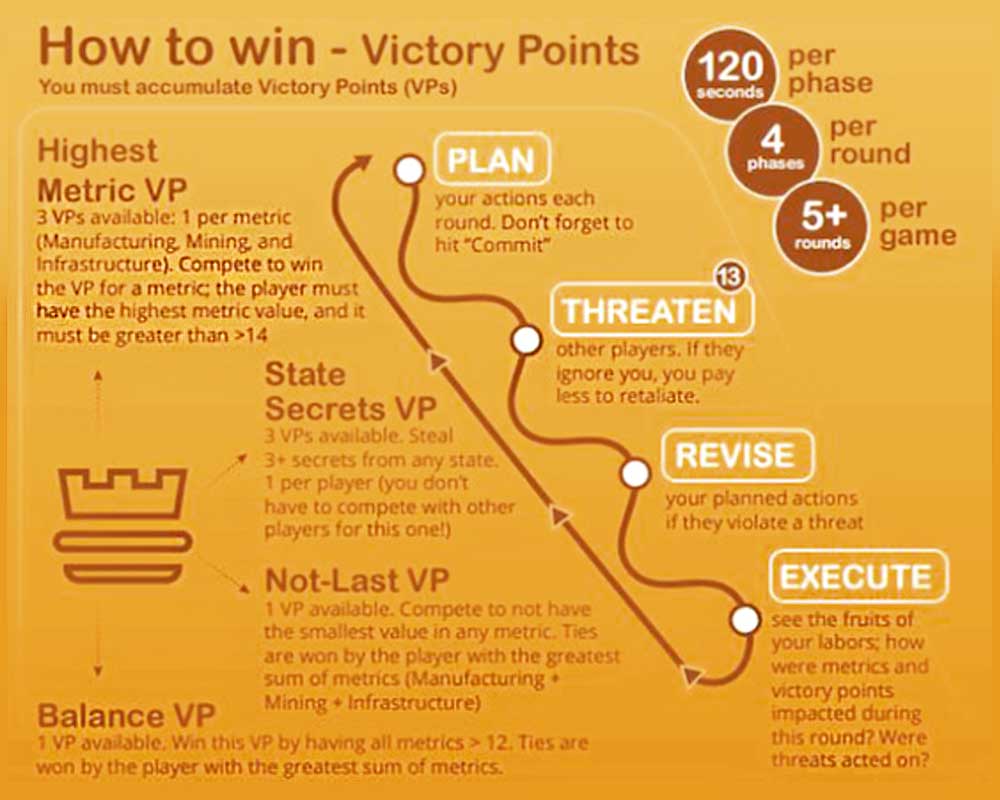

Tantalus is a three-player war game where players navigate between building and defending their nation. Players act as the leader of a hypothetical country with a mission to increase key “metrics” in their country’s mining, infrastructure and manufacturing while fending off attacks from rival countries. The game consists of 12 to 18 randomly selected rounds, with four phases per round: Planning, Threats, Revision and Execution. Players choose to influence or deter each other by force (kinetic, cyber or nuclear) or engage in espionage.

“We wanted to have the players strive for something that could be taken out of reach by the other players,” Jon said.

During the game, players might threaten to conduct a cyberattack, also known as cyber brandishing. However, in cyberwarfare, revealing a threat can decrease its effectiveness and render the threat powerless, causing a capability-communication tradeoff. Researchers analyzed the game’s data to see how this tradeoff impacted the players’ strategies and ability to manage cyberattacks, including the efficacy of threatening opponents.

“We modify game conditions by altering the available threats to player groups. We examine the gameplay across different conditions to see if players favor certain deterrence measures and how other players respond to those threats,” Jon said.

Players must earn three victory points to win, and there can be multiple winners — or no victors at all.

Vanguards of experimental war gaming

The game developers are taking a novel approach because there is little theoretical data about cyberwarfare. The team created Tantalus to study aspects of cyberdeterrence theory that are difficult to observe due to a lack of established precedence.

“Cyberweapons are very tantalizing,” Jason said. “People are constantly talking about cyberwar and cyberattacks, and it’s very tempting to try and think about that in the deterrent space. But we don’t understand it well enough to have a solid set of theories about it.”

Simulating war games in a laboratory environment allowed researchers to answer questions about the impacts on strategic stability and international and national security. The challenge was designing the type of game that would enable researchers to collect and analyze data about human behavior within a well-designed cyberworld.

“It’s exciting because it is bringing all these different facets like game developers to data scientists to machine learning folks,” Jon said.

Researchers spent the first year studying cyberdeterrence and partnering with cybersecurity experts and academics from the University of Illinois, Purdue University and the University of California, Berkeley. Then, they designed a working prototype of the game before releasing Tantalus to the public for experimental gameplay. The result was 394 games played with over 1,000 players. The data collected will allow Sandia researchers to study parts of cyberdeterrence theory that are otherwise difficult to observe.

“Some of the ideas we’ve been developing are being taken up by other organizations and academic institutions,” principal investigator Kiran Lakkaraju said. “We’re really pushing forward the field of war gaming and are on the cutting edge at Sandia.”

Tantalus is still available for all to play. The game was picked as a finalist to compete at the Serious Games Showcase & Challenge held at the I/ITSEC 2023 conference in Orlando, Florida, from Nov. 27 to Dec. 1.