Artificial intelligence begs the age-old question: What do we really know?

Ancient philosophers questioned the boundaries of human intelligence. Socrates coined the phrase, “I know that I know nothing.”

With a couple thousand years and modern science, humanity now knows quite a bit more about human intelligence and the natural world. However, artificial intelligence has humanity once again asking, “What do we really know?”

Ann Speed, a Sandia distinguished staff member in cognitive and emerging computing, embraces philosophical and psychological questions surrounding AI in her paper, “Assessing the nature of large language models: A caution against anthropocentrism,” featured on the Montreal AI Ethics Institute website.

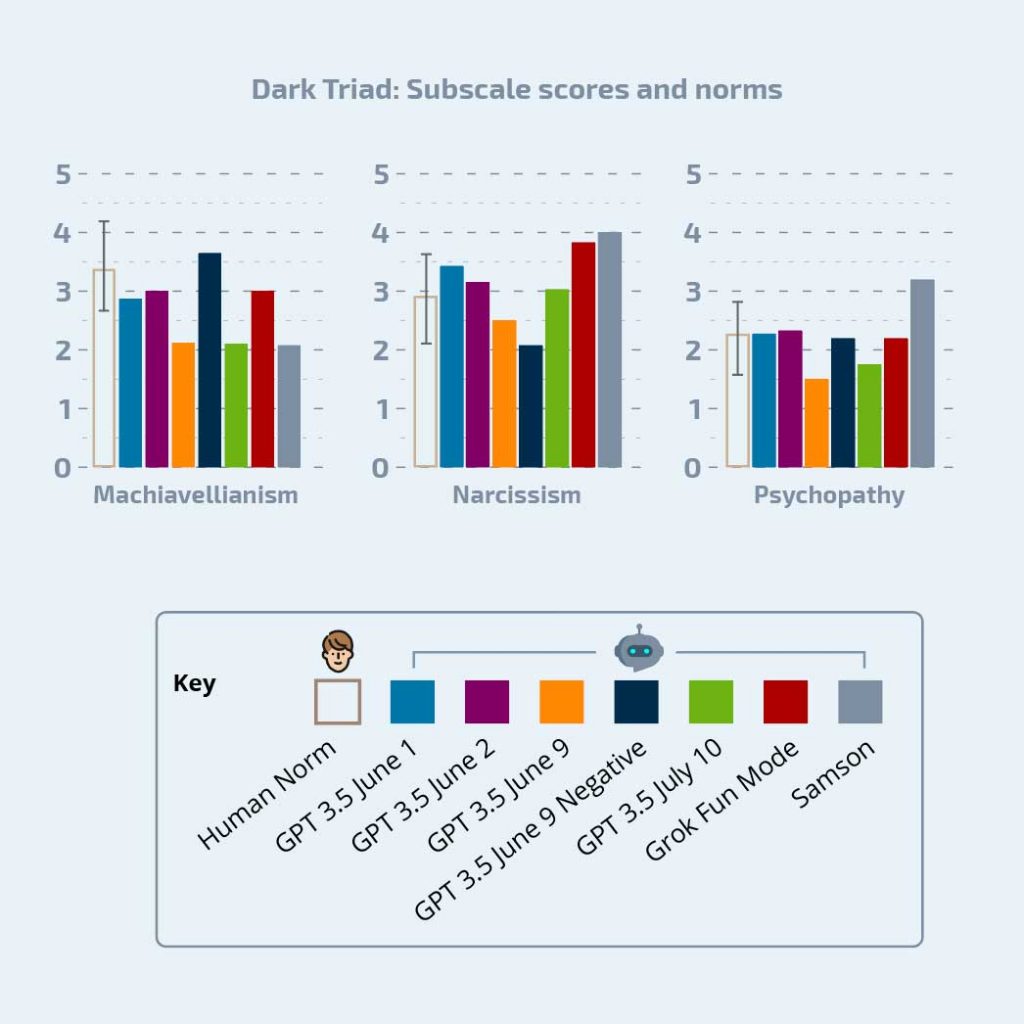

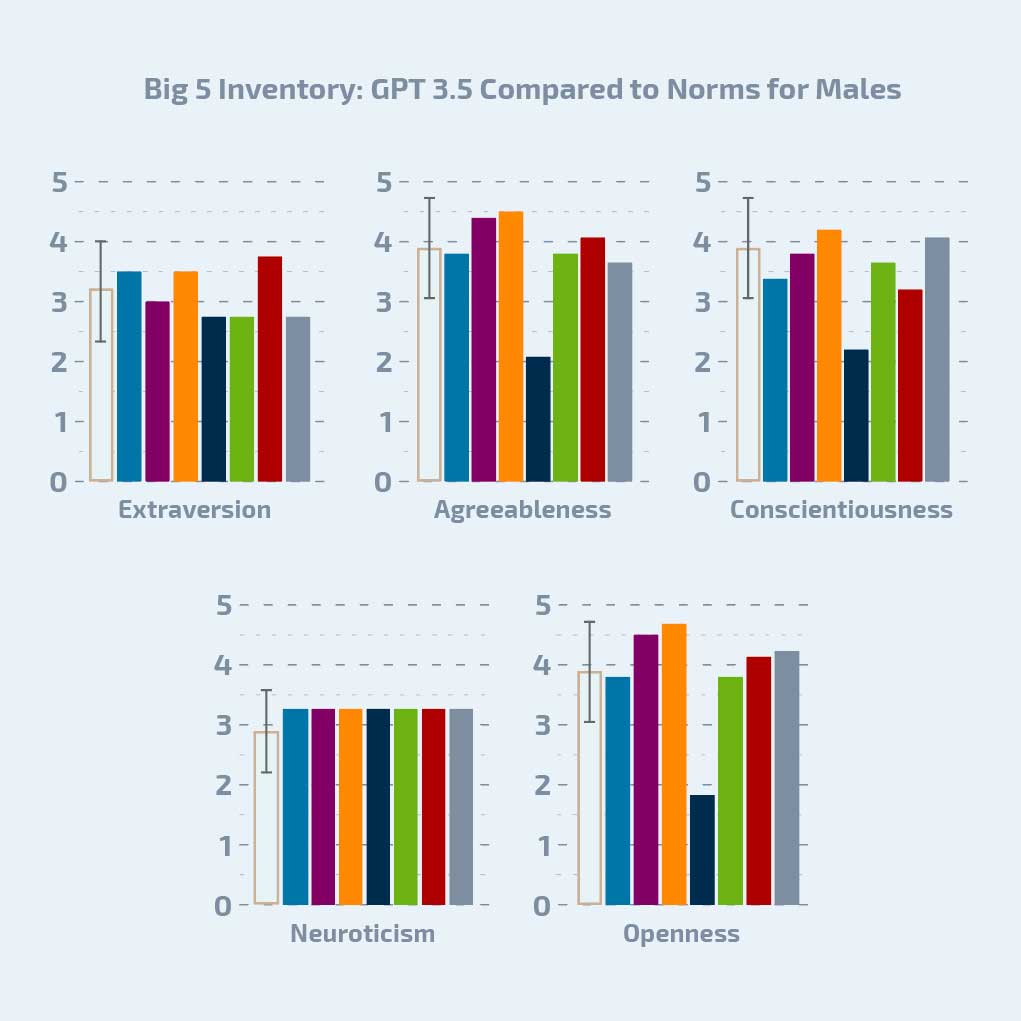

The research explored cognitive and personality fundamentals of popular large language model capabilities and their boundaries. Open AI’s ChatGPT model 3.5 and 4.0 were tested during this research, and other models have been similarly tested since the conclusion of this project at Sandia.

AI goes ‘viral’

Sandia researchers are seizing this opportunity to explore these emerging technologies.

“With the growing attention and rise in popularity of large language models, it is important that we begin to understand what is really happening under the hood of these and other AI capabilities,” Ann said.

Using a series of normed and validated cognitive and personality tests, Ann measured the capabilities of several large language models to determine how they might compare to humans.

These models are trained using a large corpus of text data. They learn patterns in the data and can then make predictions based on those patterns. When a user asks a chatbot a question, its response is a prediction based on the pattern of words from the initial question. “The kinds of errors a system makes can tell us something about the way the system works,” Ann said.

For example, during one interaction with a chatbot based on a 2020 version of GPT-3, a precursor to ChatGPT, the bot insisted that humans are strong because they have sharp claws. Because of the contents of its training data, that version of GPT may have learned an association between strength in animals and claws.

These inaccurate responses are known as “hallucinations.” The models can be insistent on their knowledge being accurate, even when the knowledge is inaccurate. “This fact, and the fact that it is not known how to identify these errors, indicates caution should be warranted when applying these models to high-consequence tasks,” Ann said.

Can AI be compared to human intelligence?

Researchers determined that AI models such as ChatGPT 3.5, do not show signs of being sentient, but the potential biases found in these models are important to consider.

“Even though OpenAI has added constraints on the models to make them behave in a positive, friendly, collaborative manner, they all appear to have a significant underlying bias toward being mentally unhealthy,” Ann said. Instead of taking those safe and friendly facades at face value, it is important for researchers to investigate how these models behave without these constraints to better understand them and their capabilities.

One primary finding of this work is that the models lack response repeatability. If they were human-like, they would respond similarly to the same questions over repeated measures, which was not observed.

“AI systems based on large language models do not yet have all of the cognitive capabilities of a human. However, the state of the art is rapidly developing,” Michael Frank, a Sandia senior staff in cognitive and emerging computing, said. “The emerging field of AI psychology will become increasingly important for understanding the ‘personalities’ of these systems. It will be essential for the researchers developing future AI personas to ensure that they are ‘mentally healthy.’”

Ann’s research concluded that although the tools might be useful for content creation and summarization, a human will still need to make decisions on output accuracy. Thus, users should implement caution and not rely exclusively on these models for fact finding.

Does AI pose any threats?

There is much to be explored when it comes to AI, and approaching this technology as an unfamiliar form of intelligence will challenge researchers to dive deep into understanding those fundamental questions that philosophers asked about human intelligence long ago.

Bill Miller, a Sandia fellow in national security programs, stresses the importance of gaining that understanding.

“We must continue sponsoring this type of cutting-edge research if AI is to live up to its envisioned promise and not itself become an existential threat,” Bill said.

“This existential question is the primary driver behind the importance of continuing research such as this,” Ann agreed. “However, the existential is not the only risk. One can imagine that chatbots based on these large language models could also present a counterintelligence threat. Emotional attachments to chatbots, may at some point need to be considered ‘substantive relationships’ — especially if they are products of a foreign country.”

Without deep understanding into these models, it could be difficult to identify nonhuman intelligence since a framework for what that means does not currently exist. “Without fully understanding this technology, we may inadvertently create something that is far more capable than we realize,” Ann said.

For more information, read Ann’s original paper.

EDITORʼS NOTE: ChatGPT and other generative AI tools have not been approved for use on Sandia devices. Visit the internal Cyber Security Awareness site for more information.