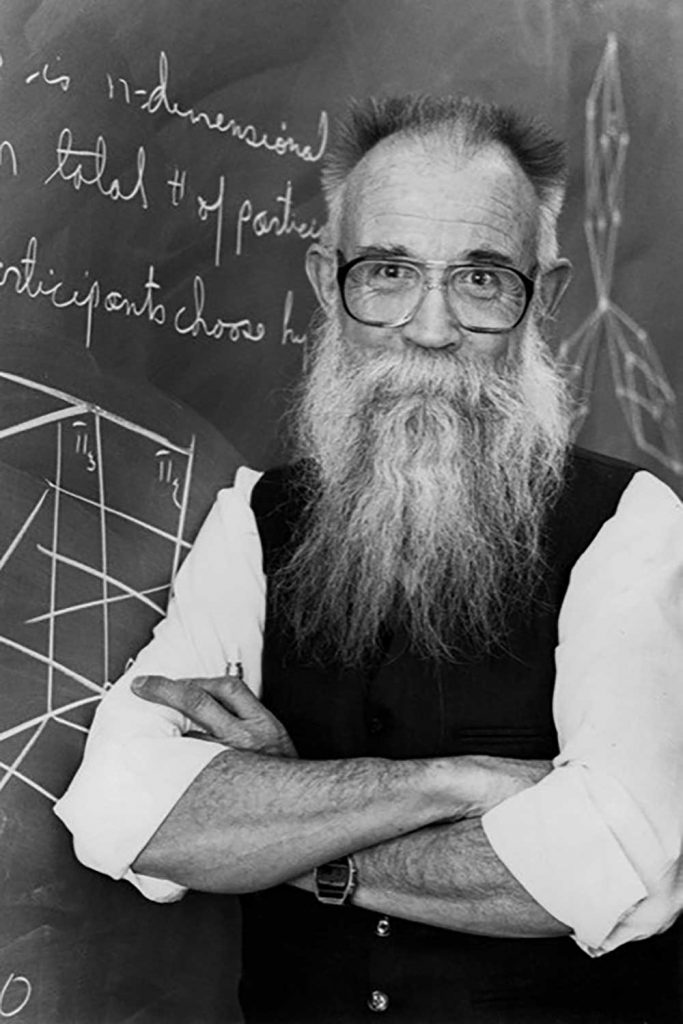

First Sandia Fellow talks about his remarkable career, and one problem he never solved

Gus Simmons, 93, said he wouldn’t believe his own story if he hadn’t lived it.

Seventy years after Sandia first hired him (the Labs would eventually hire him three more times), the E.O. Lawrence Award winner and Sandia’s first Fellow shared with me a far-flung career that established him as a major figure in the fields of command and control, cryptology and authentication.

And although he has finally been settling into his full retirement, he also shared one unsolved national security problem he says still weighs on his mind.

Simmons, a spunky West Virginian storyteller, zips from tale to tale throughout our conversation, apologizing but not stopping when he strays from my questions. He retired from Sandia in 1993 but only stopped publishing math papers a few years ago.

“From the neck up I’m in pretty good shape,” he said.

Now living in Los Lunas, New Mexico, with his partner, Helen, and their Rhodesian Ridgeback, he said he looks back at his career with immense satisfaction.

“I was able to do just what I would have done if I were rich and could have done whatever I wished,” he said.

Here and gone again

It was 1955. Eisenhower was President. Rosa Parks had been arrested. The first McDonald’s had started selling hamburgers. And Gus Simmons, a Sandia technician, did something that would shape history, too.

He quit his job.

It was a curious career move for someone who had accomplished so much just to get where he was. Simmons was born in 1930 in a rural coal mining town, or as he described it, “The worst place in the country to be born.”

(Simmons elaborates on his childhood in his memoir “Another Time, Another Place, Another Story.” Click on the first cover photo for the book.)

But Simmons was a go-getter with an insatiable curiosity and intellect. When he was 16, he was one of 40 national winners of the Westinghouse Science Talent Search, which earned him a picture with President Truman and enough prize money to move to California for college.

Unfortunately, when his plans went awry, he wound up homeless on the streets of Los Angeles. He didn’t know a soul, had no way or money to get home and no job experience to fall back on.

His ticket out of homelessness was acing a competitive math and science test that got him into the newly formed Air Force, beating throngs of GIs returning from World War II, many hoping to reenlist.

“Not only did it save me from being homeless in L.A., it was the entrée — my years of college-level training in electrical engineering and five years of experience in the Air Force as a radar technician — that led to me being hired at Sandia. So, the Barksdale AFB acceptance letter was the most important thing in my entire life,” Simmons said.

“I couldn’t even guess what would have happened to me if that hadn’t happened.”

Simmons joined Sandia as a technician in 1954. His position was low-paying and precarious. A scientist he was working under fired him on the spot when an experimental computer failed during a demonstration for his management. Simmons arranged with the personnel office to simply move to a different organization under the condition that the scientist could never know Simmons was still employed at Sandia.

When Simmons learned he had no hope of promotion without an advanced degree, he quit, setting in motion a remarkable scientific career and his impact on U.S. national security.

Innovating in satellites, weapons, mathematics and more

Simmons earned a bachelor’s degree in math and physics from New Mexico Highlands University, and returned to Sandia in 1958 after completing his master’s degree in physics from the University of Oklahoma.

With diplomas in hand, Simmons went to work on the Vela Hotel program, Sandia’s first foray into designing satellites for detecting nuclear detonations. The program was so successful he was poached by the McDonnell Aircraft Corp. to work as a group manager on the first U.S. human spaceflight program, Mercury.

Simmons returned to Sandia again in the 1960s to lead a group mandated by President John F. Kennedy to get U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe under positive control.

“What that means is separating the possession of a nuclear weapon from the ability to use it as a nuclear weapon,” said Simmons.

“For the next five years, I worked quite literally night and day on the program.”

In the end, Simmons’ group developed the nuclear stockpile’s first permissive action link, commonly called a PAL — an electromechanical lock that stops unauthorized individuals from using a nuclear weapon.

“That’s what got me the (E.O.) Lawrence Award. That’s what got me the Department of Defense Award of Excellence. In a sense, that got me the honorary doctorate (from Lund University). It was pivotal to my whole life,” Simmons said.

After earning a doctoral degree in Math from the University of New Mexico, he quit Sandia a third time, in 1969 to help form a tech company, Rolamite, Inc.; returning after the company was “eaten alive” in a hostile stock takeover.

During his fourth and final stay at Sandia, he designed a Mars lander, achieved a mathematical breakthrough by factoring a 69-digit number and developed numerous authentication protocols critical to maintaining nuclear arms treaties, now used extensively for e-commerce.

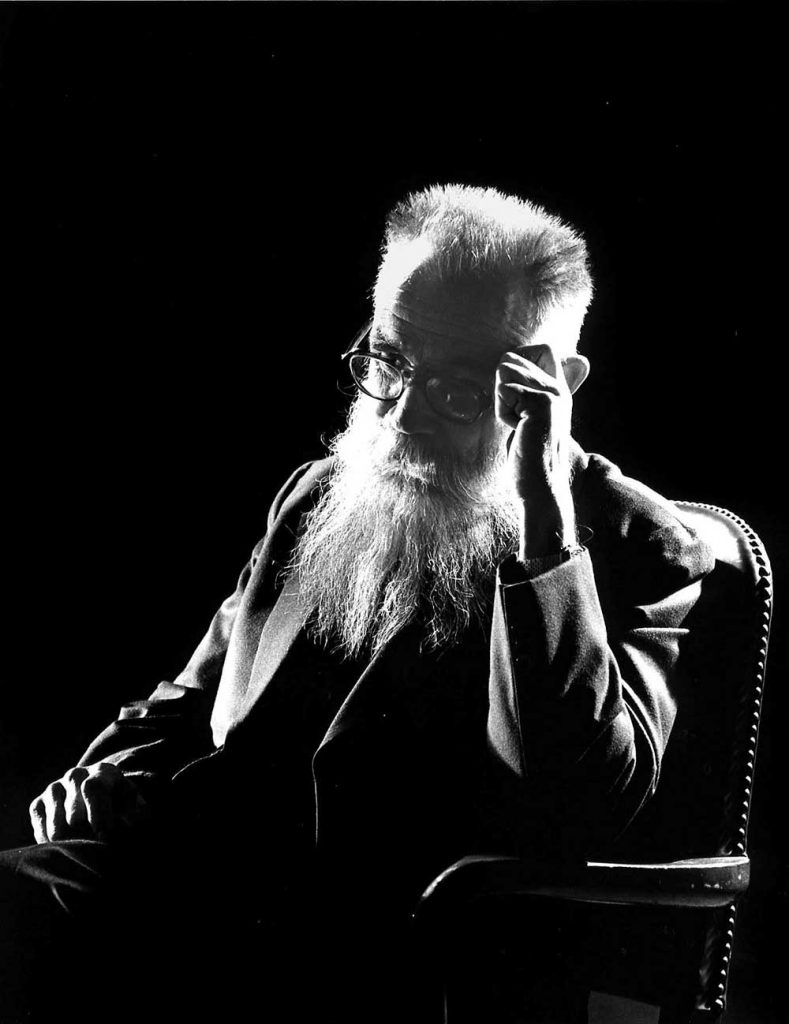

A still unanswered question

(Photo by Randy Montoya)

In 1986, Sandia president Irwin Welber announced the creation of a new position — Senior Fellow, now called Sandia Fellow. In the Lab News, Welber was quoted saying the position was “to recognize a very limited number of technical professional staff who have demonstrated continuing contributions of truly exceptional breadth, depth, and creativity in fields impacting the technical mission of the Labs.”

Simmons was recognized as Sandia’s first Fellow.

“I don’t anticipate many Senior Fellows in the future,” Welber said at the time. There have been 21 in Sandia’s history. In 2023, Labs Director James Peery expanded the program to include non-research and development positions.

In his new position, Simmons reported directly to Sandia’s president. He focused his efforts on studying how to relock unexpended nuclear weapons after some have already been used in a conflict, a problem needing technology that wasn’t available during his career.

“No, I was unsuccessful. We have an enormous amount of research on how you escalate to a nuclear war and how you control the use of nuclear weapons. What I realized was there was absolutely nothing on the converse. How do you scale back?” Simmons said.

He and others did make progress in some aspects of deescalating a nuclear war. One option Simmons studied was “selective release” codes that could arm some nuclear weapons but not others, giving governments the ability to limit warfare. But, during his time at Sandia he did not find an effective mechanism for a president to reestablish positive control on weapons that had been unlocked.

“It is an absolutely vital problem for the welfare of mankind. If we ever use nuclear weapons — actually use them — how do they step back from it? How do they scale back? How do they end it?”

Would he do it all again?

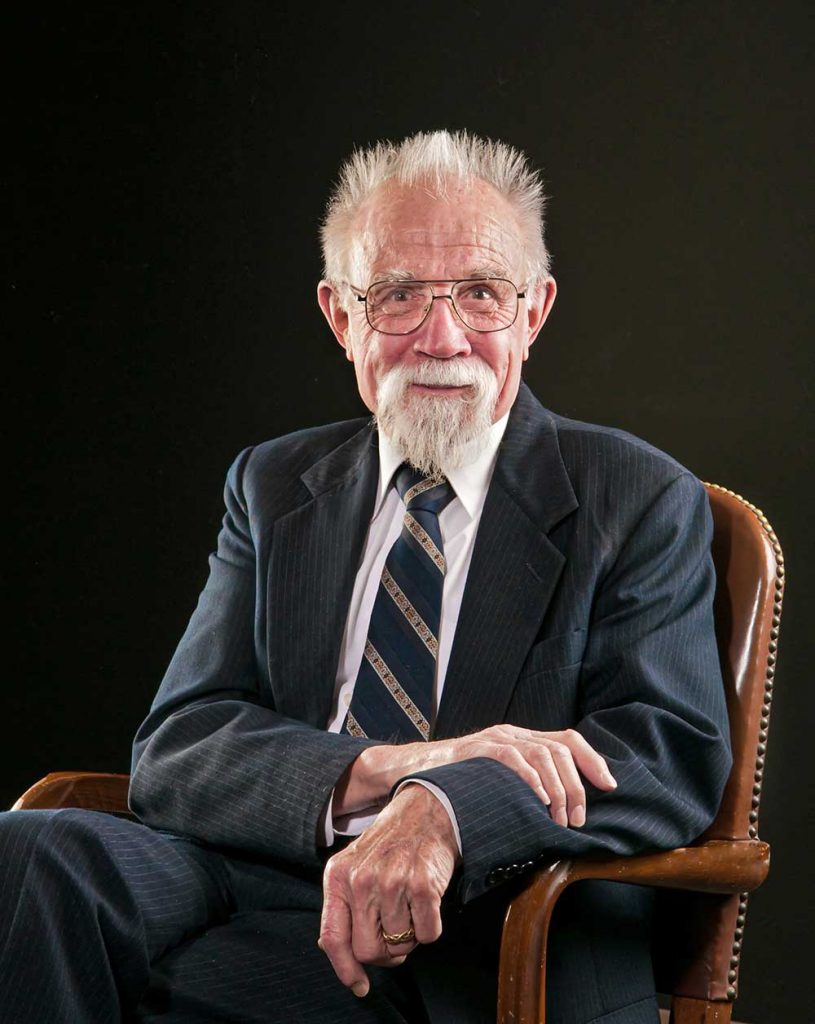

Simmons retired from Sandia in 1993 but afterward enjoyed nearly three decades of prolificity in academia. He served in distinguished positions at Lund University in Sweden; Royal Holloway, University of London, in Windsor, U.K.; and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany. He was appointed the Rothschild Professor of Mathematics at the Newton Institute of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Trinity College. He also won the University of New Mexico Zimmerman Award.

“I had three papers published two years ago, math papers, and one of those is perhaps the best paper of my math career,” he said.

Now, at last, Simmons says his story is coming to a close.

“Lord, I wish I were starting over. Well, not starting over, but —” for the first time in our conversation, Simmons fumbles for his words. Then he finds them. “It’s been an incredible experience.”