Scientists study clay for snatching carbon dioxide from air

The atmospheric level of carbon dioxide — a gas that is great at trapping heat, contributing to climate change — is almost double what it was prior to the Industrial Revolution, yet it only constitutes 0.0415% of the air we breathe.

This presents a challenge to researchers attempting to design artificial trees or other methods of capturing carbon dioxide directly from the air. That challenge is one a Sandia-led team of scientists is attempting to solve.

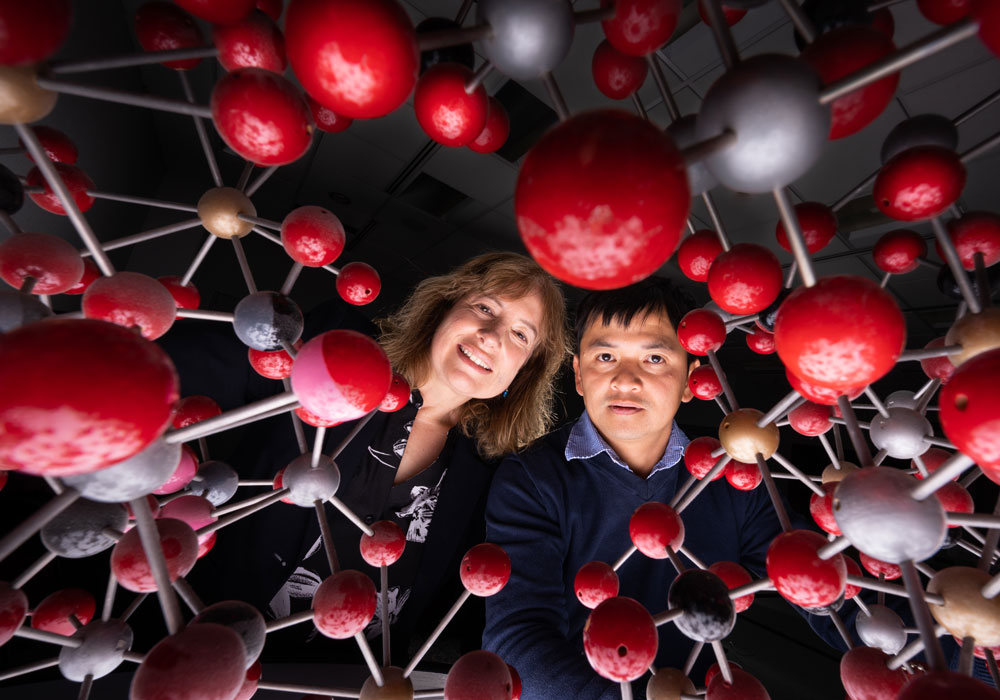

Led by chemical engineer Tuan Ho, the team has been using powerful computer models combined with laboratory experiments to study how a kind of clay can soak up carbon dioxide and store it.

The scientists shared their initial findings in a paper published Feb. 9 in The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

“These fundamental findings have potential for direct-air capture; that is what we’re working toward,” said Tuan, lead author on the paper. “Clay is really inexpensive and abundant in nature. That should allow us to reduce the cost of direct-air carbon capture significantly, if this high-risk, high-reward project ultimately leads to a technology.”

Why capture carbon?

Carbon capture and sequestration is the process of capturing excess carbon dioxide from the Earth’s atmosphere and storing it deep underground with the aim of reducing the impacts of climate change, such as more frequent severe storms, rising sea levels and increased droughts and wildfires. This carbon dioxide could be captured from fossil-fuel-burning power plants, or other industrial facilities such as cement kilns, or directly from the air, which is more technologically challenging. Carbon capture and sequestration is widely considered one of the least controversial technologies being considered for climate intervention.

“We would like low-cost energy, without ruining the environment,” said Susan Rempe, a Sandia bioengineer and senior scientist on the project. “We can live in a way that doesn’t produce as much carbon dioxide, but we can’t control what our neighbors do. Direct-air carbon capture is important for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the air and mitigating the carbon dioxide our neighbors release.”

Tuan imagines that clay-based devices could be used like sponges to soak up carbon dioxide, and then the carbon dioxide could be “squeezed” out of the sponge and pumped deep underground. Or the clay could be used more like a filter to capture carbon dioxide from the air for storage.

In addition to being cheap and widely available, clay is also stable and has a high surface area — it is composed of many microscopic particles that in turn have cracks and crevasses about a hundred thousand times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. These tiny cavities are called nanopores, and chemical properties can change within these nanoscale pores, Susan said.

This is not the first time Susan has studied nanostructured materials for capturing carbon dioxide. In fact, she is part of a team that studied a biological catalyst for converting carbon dioxide into water-stable bicarbonate, tailored a thin, nanostructured membrane to protect the biological catalyst and received a patent for their bio-inspired, carbon-catching membrane. Of course, this membrane is not made of inexpensive clay and was initially designed to work at fossil-fuel-burning power plants or other industrial facilities, Susan said.

“These are two complementary possible solutions to the same problem,” she said.

How to simulate the nanoscale?

Molecular dynamics is a kind of computer simulation that looks at the movements and interactions of atoms and molecules at the nanoscale. By looking at these interactions, scientists can calculate how stable a molecule is in a particular environment — such as in clay nanopores filled with water.

“Molecular simulation is really a powerful tool to study interactions at the molecular scale,” Tuan said. “It allows us to fully understand what is going on among the carbon dioxide, water and clay, and the goal is to use this information to engineer a clay material for carbon-capture applications.”

In this case, the molecular dynamics simulations conducted by Tuan showed that carbon dioxide can be much more stable in the wet clay nanopores than in plain water, he said. This is because the atoms in water do not share their electrons evenly, making one end slightly positively charged and the other end slightly negatively charged. On the other hand, the atoms in carbon dioxide do share their electrons evenly, and like oil mixed with water, the carbon dioxide is more stable near similar molecules, such as the silicon-oxygen regions of the clay, Susan said.

Collaborators from Purdue University led by professor Cliff Johnston recently used experiments to confirm that water confined in clay nanopores absorbs more carbon dioxide than plain water does, Tuan said.

Sandia postdoctoral researcher Nabankur Dasgupta also found that inside the oil-like regions of the nanopores, it takes less energy to convert carbon dioxide into carbonic acid and makes the reaction more favorable compared to the same conversion in plain water, Tuan said. By making this conversion favorable and require less energy, ultimately the oil-like regions of clay nanopores make it possible to capture more carbon dioxide and store it more easily, he added.

“So far, this tells us clay is a good material for capturing carbon dioxide and converting it into another molecule,” Susan said. “And we understand why this is, so that the synthesis people and the engineers can modify the material to enhance the oil-like surface chemistry. The simulations can also guide the experiments to test new hypotheses about how to promote the conversion of carbon dioxide into other valuable molecules.”

The next steps for the project will be to use molecular dynamics simulations and experiments to figure out how to get carbon dioxide back out of the nanopore, Tuan said. By the end of the three-year project, they plan to conceptualize a clay-based direct-air carbon capture device.

The project is funded by Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program. The research was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE by Sandia and Los Alamos national laboratories.