It may not be common knowledge within Sandia that the Labs are home to the Plasma Research Facility. However, those who study plasma around the nation and the world are not only acutely aware, but they are also coming in great numbers to perform experiments and work with the experts.

“There are critical technologies in the world — anything with a microchip in it — that are based on plasma science. Manufacturing chips requires plasmas,” said Shane Sickafoose, administrative head of the program.

The Sandia facility was fully funded by the DOE’s Fusion Energy Sciences program in fall 2019.

“The depth and breadth of Sandia’s technical expertise and facilities enable collaborations not possible anywhere other than at a national laboratory,” Shane said. “The ability to have a team of experts in both experimental and modeling-simulation efforts focused on a problem is truly unique.”

So, the team started to invite collaborators.

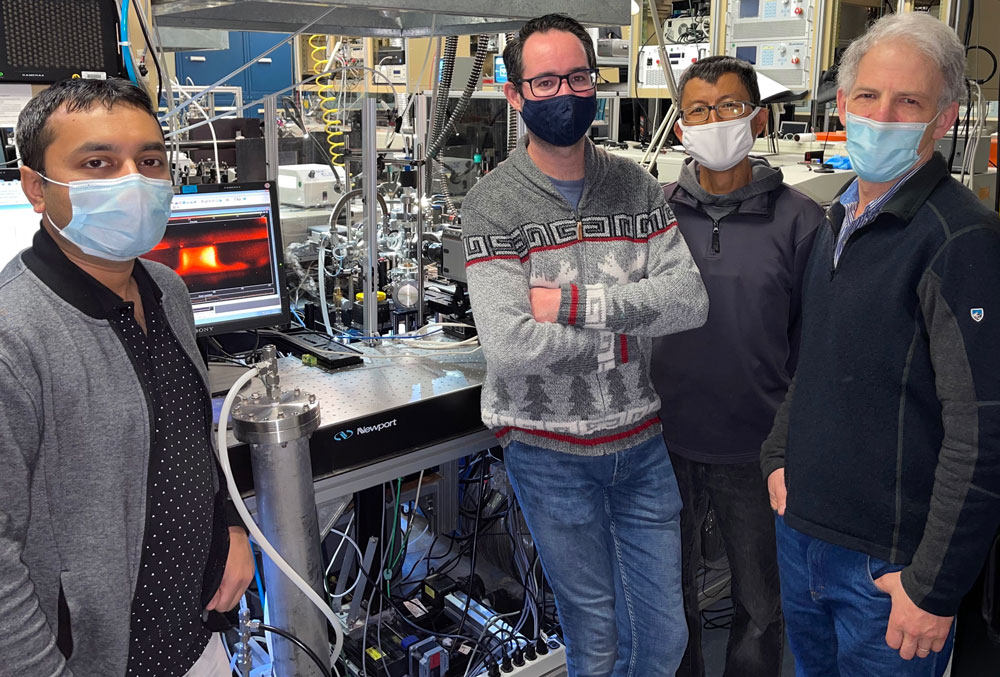

“The overall idea was that there would be proposals from universities, other national labs, both in the U.S. and abroad, to do collaborative research,” said manager Nils Hansen, who was part of the facility from the start and helped write the funding proposal. “My first user was professor Yiguang Ju from Princeton University. He was studying plasma chemical looping. We chose him because he had a compelling argument that he was stuck with the instrumentation at Princeton and wanted to take advantage of what we had here at this facility.”

Tackling new problems in new ways

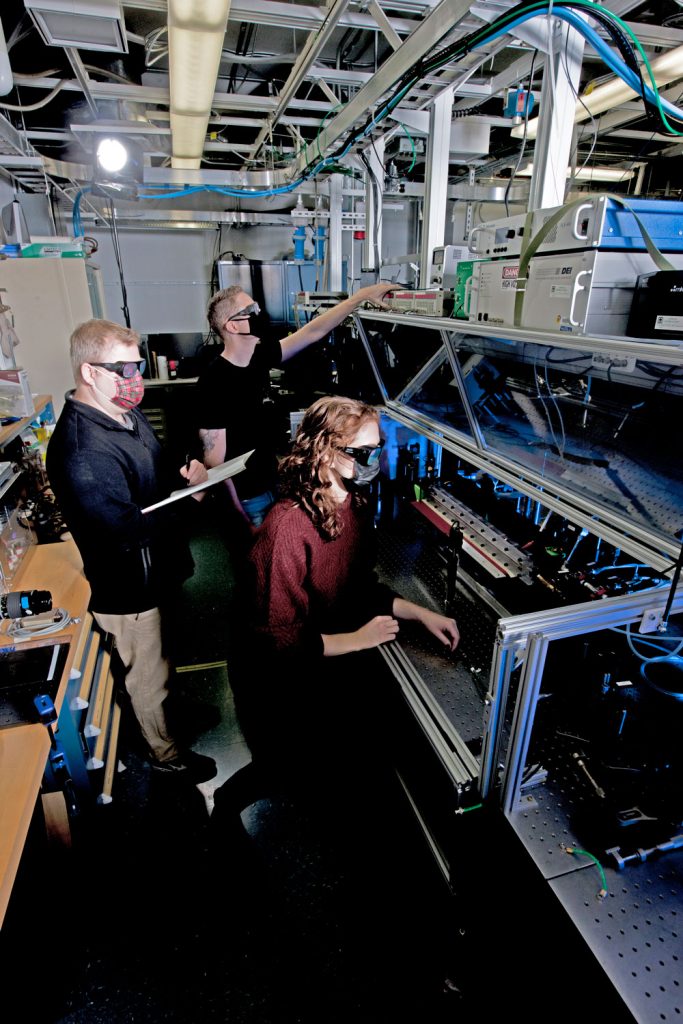

Since then, even throughout the pandemic, the Plasma Research Facility has been able to host multiple scientists studying a variety of plasma effects. Plasma scientist Jonathan Frank, who also helped write the funding proposal, said some of the studies have been directly influenced by urgent needs.

“The second user I hosted was professor Tanvir Farouk from the University of South Carolina,” Jonathan said. “He and his student Malik Tahiyat were looking at the effects of having water vapor in a plasma, which could be used for treatments of heat-sensitive surfaces, including sterilization of contaminated surfaces. The pandemic made research related to killing viruses on surfaces particularly relevant.”

Sandia chemistry researcher Chris Kliewer also hosted the growing network of collaborators. He said that in the last couple of years, only U.S.-based scientists could easily come to do work at the Plasma Research Facility. That is changing.

“On the next round, a number of people were coming from overseas,” Chris said. “It’s kind of interesting that the proposals we are seeing to do research here are ones that span a couple of our labs within the facility because they have multiple interests and goals.”

Bringing computer power to bear

Sandia modeler Matt Hopkins added that the experimental capabilities are linked with a capability most labs lack: advanced simulation capabilities and algorithms, the robust computational power to take advantage of them and experienced modelers who know how to maximize computing capabilities.

“We have multiple high-performance computing platforms — an astounding amount of computing resources available,” he said. “We have simulation codes that have benefited from decades of DOE investments. They have access to world-leading experts to harness that computing power.”

And it is that breadth of capabilities that Matt believes will benefit the entire sector of plasma research.

“I’ve been in the low-temperature plasma community since the last millennium. It can be extremely difficult to collaborate with folks outside the Labs, but the Plasma Research Facility has set up a venue for that,” he said. “There are very, very few places that have all of these things: the computational machine, the fancy code and the experts. The plasma problems that they are modeling, being able to solve problems at the scale that we can, it’s just not something a lot of people have access to.”

People at the heart of the facility

Jonathan underscored Matt’s point that the Plasma Research Facility is about more than technological capabilities. “It’s not just the equipment — it’s the expertise that has been developed over a long time,” he said. “Now we are developing new capabilities as we get new users.”

Nils agreed. “We’ve definitely had examples of proposals we never thought of. This is something we would never have started without the user proposal. We wanted to help the plasma community as a whole,” he said.

Matt sees a broad future of innovation and invention coming from the Plasma Research Facility.

“There are a lot of current industrial uses — semiconductor manufacturing, lighting, medical applications,” he said. “But this is just the beginning. Think of fantastical things: thrusters like you would see in Star Wars or new applications like nanoparticle synthesis, medical sterilization techniques or virus decontamination from plasmas. There is a frontier of new applications for plasma that are becoming important.”

The new facility brings Sandia to the forefront of that frontier.