Discovery leads developers to software fix

Sandia researchers have identified a weakness in one common open-source software for genomic analysis that left DNA-based medical diagnostics vulnerable to cyberattacks.

The researchers notified the software developers, who issued a patch to fix the problem, and the issue has been fixed in the latest release of the software. While no attack from this vulnerability is known, the National Institutes of Standards and Technology recently described it in a note to software developers, genomics researchers and network administrators.

The discovery reveals that protecting genomic information involves more than safe storage of an individual’s genetic information. The cybersecurity of computer systems analyzing genetic data is also crucial, said Corey Hudson, a Sandia bioinformatics researcher who helped uncover the issue.

Personalized medicine — the process of using a patient’s genetic information to guide medical treatment — involves two steps: sequencing the entire genetic content from a patient’s cells and comparing that sequence to a standardized human genome. Through that comparison, doctors identify specific genetic changes in a patient that are linked to disease.

Genome sequencing starts with cutting and replicating a person’s genetic information into millions of small pieces. Then a machine reads each piece numerous times and transforms images of the pieces into sequences of building blocks, commonly represented by the letters A, T, C and G. Finally, software collects those sequences and matches each snippet to its place on a standardized human genome sequence. One matching program used widely by personalized genomics researchers is called the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.

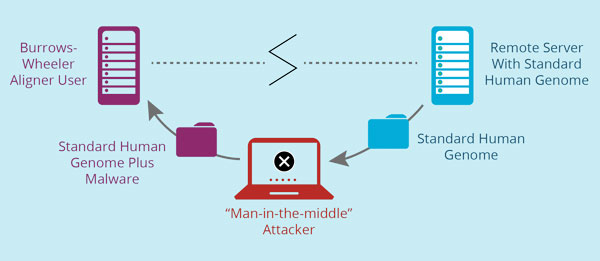

Sandia researchers studying the cybersecurity of this program found a weak spot when the program imported the standardized genome from government servers. The standardized genome sequence traveled over insecure channels, which created the opportunity for a common cyberattack called a “man-in-the-middle.”

In this attack, an adversary or a hacker could intercept the standard genome sequence and then transmit it to a BWA user along with a malicious program that alters genetic information obtained from sequencing. The malware could then change a patient’s raw genetic data during genome mapping, making the final analysis incorrect without anyone knowing it. Practically, this means doctors may prescribe a drug based on the genetic analysis that, had they had the correct information, they would have known would be ineffective or toxic to a patient.

Forensic labs and genome sequencing companies that use this mapping software were also temporarily vulnerable to having results maliciously altered in the same way. Information from direct-to-consumer genetic tests was not affected by this vulnerability because these tests use a different sequencing method than whole genome sequencing, Corey said.

To find this vulnerability, Corey and his cybersecurity colleagues at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign used a platform developed by Sandia called Emulytics to simulate the process of genome mapping. First, they imported genetic information simulated to resemble that from a sequencer. Then they had two servers send information to Emulytics. One provided a standard genome sequence and the other acted as the “man-in-the-middle” interceptor. The researchers mapped the sequencing results and compared results with and without an attack to see how the attack changed the final sequence.

“Once we discovered that this attack could change a patient’s genetic information, we followed responsible disclosure,” Corey said. The researchers contacted the open-source developers, who then issued a patch to fix the problem. They also contacted public agencies, including cybersecurity experts at the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team, so they could more widely distribute information about this issue.

The research, funded by Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program, will continue to test other genome-mapping software for security weaknesses. Differences between each computer program mean the researchers might find a similar, but not identical, issue, Corey said.

Along with installing the latest version of BWA, Corey and his colleagues recommend other “cyber hygiene” strategies to secure genomic information, including transmitting data over encrypted channels and using software that protects sequencing data from being changed. They also encourage security researchers who routinely analyze open-source software for weaknesses to look at genomics programs. This practice is common in industrial control systems in the energy grid and software used in critical infrastructure, Corey said, but would be a new area for genomics security.

“Our goal is to make systems safer for people who use them by helping to develop best practices,” he said.