A biologically inspired membrane intended to cleanse carbon dioxide almost completely from the smoke of coal-fired power plants has been developed jointly by researchers at Sandia and the University of New Mexico.

The patented work, reported recently in “Nature Communications,” has interested power and energy companies that would like to significantly reduce emissions of carbon dioxide, one of the most widespread greenhouse gases, and explore other possible uses of the invention.

Researchers term the membrane a “memzyme” because it acts like a filter and is near-saturated with an enzyme, carbonic anhydrase, developed by living cells over millions of years to help rid themselves of carbon dioxide efficiently and rapidly.

“To date, stripping carbon dioxide from smoke has been prohibitively expensive using the thick, solid, polymer membranes currently available,” says Jeff Brinker, a Sandia fellow, University of New Mexico regents’ professor and lead author of the paper.

“Our inexpensive method follows nature’s lead in our use of a water-based membrane only 18 nanometers thick that incorporates natural enzymes to capture 90 percent of carbon dioxide released. (A nanometer is about 1/700 of the diameter of a human hair.) This is almost 70 percent better than current commercial methods, and it’s done at a fraction of the cost.”

Coal power plants are one of the U.S.’s largest energy resources, but they face regulatory hurdles and criticism for sending more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than any other form of electrical power generation. Still, coal burning in China, India and other countries means that U.S. abstinence alone is unlikely to solve the world’s climate problems.

But, says Jeff, “maybe technology will.”

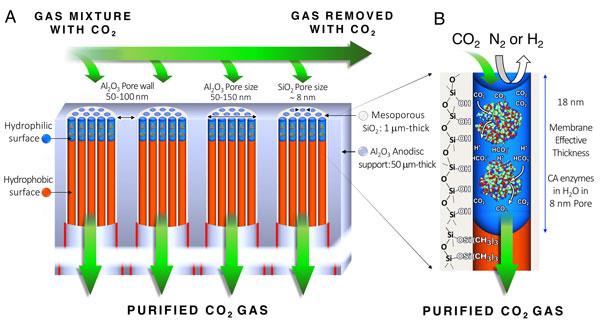

Enzymatic liquid membrane design and mechanism of carbon dioxide capture and separation:

The Sandia/UNM membrane is fabricated by formation of 8-nanometer diameter cylindrical mesopores. Using atomic layer deposition and oxygen plasma processing, the silica mesopores are engineered to be hydrophobic except for an 18-nanometer-deep region at the pore surface which is hydrophilic. Through capillary condensation, carbonic anhydrase enzymes and water spontaneously fill the hydrophilic mesopores to form an array of stabilized enzymes with an effective concentration greater than 10 times of that achievable in solution. These catalyze the capture and dissolution of carbon dioxide at the upstream surface and regeneration of carbon dioxide at the downstream surface. The high enzyme concentration and short diffusion path maximizes capture efficiency and flux. (Image courtesy of Sandia)

The memzyme meets the Department of Energy’s standards by capturing 90 percent of power plant carbon dioxide production at the relatively low cost of $40 per ton.

The device’s creation begins with a drying process called evaporation-induced self-assembly, first developed at Sandia by Brinker 20 years ago and a field of study in its own right.

The procedure creates a close-packed array of silica nanopores designed to accommodate the carbonic anhydrase enzyme and keep it stable. This is done by treating the array, which may be 100 nanometers long, with a technique called atomic layer deposition to make the nanopore surface water-averse, or hydrophobic. An oxygen plasma treatment then makes the nanopores water-loving or hydrophilic, but only to a depth of 18 nanometers. A solution of the enzyme and water fill up and are stabilized within the water-loving nanopores. This creates a membrane of water 18 nanometers thick, with a carbonic anhydrase concentration 10 times greater than any aqueous solution made to date.

The solution, at home in its water-loving sleeve, is stable. But because the enzyme can rapidly and selectively dissolve carbon dioxide, the catalytic membrane has the capability to capture the overwhelming majority of carbon dioxide molecules that brush up against it from a rising cloud of coal smoke. The hooked molecules then pass rapidly through the membranes, driven solely by a naturally occurring pressure gradient caused by the large number of carbon dioxide molecules on one side of the membrane and their comparative absence on the other. The enzyme turns the gas briefly into carbonic acid and then bicarbonate before exiting immediately downstream as carbon dioxide gas.

The gas can be harvested with 99 percent purity — so pure that it could be used by oil companies for resource extraction. Other molecules pass by the membrane’s surface undisturbed. The enzyme is reusable and, because the water serves as a medium rather than an actor, does not need replacement.

“Energy companies and oil and gas utilities have expressed interest in optimizing the gas filters for specific conditions,” says Susan Rempe, Sandia researcher and co-author, who suggested and developed the idea of inserting carbonic anhydrase into the water solution to improve the speed by which carbon dioxide could be taken up and released from the membrane. “The enzyme can catalyze the dissolution of a million carbon dioxide molecules per second, vastly improving the speed of the process. With optimization by industry, the memzyme could make electricity production cheap and green,” she says.

The nanopores dry out over long periods of time due to evaporation. This will be checked by water vapor rising from lower water baths already installed in power plants to reduce sulfur emissions. And, enzymes damaged from use over time can easily be replaced.

Says Jeff, “The very high concentration of carbonic anhydrase, along with the thinness of the water channel, result in very high carbon dioxide flux through the membrane. The greater the carbonic anhydrase concentration, the greater the flux. The thinner the membrane, the greater the flux.”

The membrane’s arrangement in a generating station’s flue would be like that of a catalytic converter in a car, suggests Jeff. The membranes would sit on the inner surface of a tube arranged like a honeycomb. The flue gas would flow through the membrane-embedded tube, with a carbon dioxide-free gas stream on the outside of the tubes. Varying the tube length and diameter would optimize the carbon dioxide extraction process.

The separation process could increase the amount of fuel obtained by enhanced oil recovery using carbon dioxide injected into existing reservoirs. A slightly different enzyme, used in the same process, can convert methane — an even more potent greenhouse gas — to the more soluble methanol for removal, Susan says.

Prior cleansing by industrial scrubbers means that the rising smoke will be clean enough not to significantly impair membrane efficiency, says University of New Mexico professor and paper co-author Ying-Bing Jiang, who originated and developed the idea of using watery membranes based on the human body’s processes rather than solid manufactures, to separate out carbon dioxide. The membranes have operated efficiently in laboratory settings for months.

The procedure also could sequester carbon dioxide on a spacecraft, because the membranes operate at ambient temperatures and are driven solely by chemical gradients, say the authors.

The work was initially supported by Sandia Laboratory Directed Research and Development, with additional funding from the Department of Energy Office of Science and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. The work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated by Sandia and Los Alamos national labs.