International peer mentorship program improves global preparedness

The world is becoming increasingly interconnected. While this has definite advantages, it also makes it easier to spread disease. Many diseases don’t produce symptoms for days or weeks, far longer than international flight times. For example, Ebola has an incubation period of two to 21 days.

Improving biosafety practices around the world to prevent the spread of diseases to health care workers and biomedical researchers is an important part of halting or minimizing the next pandemic, says Eric Cook, a Sandia biorisk management expert.

In mid-October, during the American Biological Safety Association annual conference, Eric gave a plenary talk on Sandia’s biosafety peer mentorship program.

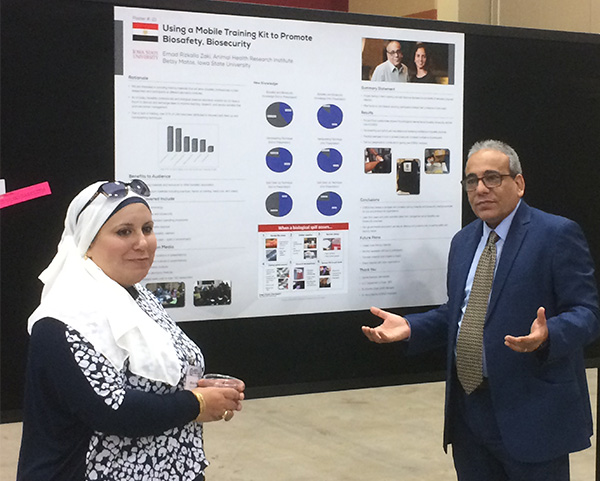

This mentoring program, called the Biosafety Twinning program, pairs experienced biosafety professionals from developed countries with their counterparts in the developing world. The twins work together over six months on self-selected projects to improve the biosafety and biosecurity of the Middle East and North Africa regional twin’s home institution or country. Posters on five of the twinning projects were also presented at the annual conference.

Experts from Sandia’s International Biological and Chemical Threat Reduction group have been working for more than 15 years to enhance global biosafety and biosecurity through this innovative mentoring program, other training programs, and biorisk manuals.

Six-month projects with substantial impacts

The Biosafety Twinning projects are planned to achieve results in six months but often grow to impact whole countries, says Eric.

Bassel Mamdouh, from Egypt’s Central Public Health Lab and a member of the second Twinning class, planned to develop a biorisk management structure for some of Egypt’s Ministry of Health labs. His project expanded to include assigning biosafety coordinators for each of the 27 regional public health laboratories, getting ministry leadership approval, determining roles and responsibilities for biosafety coordinators and officers, and ensuring they were properly trained. In addition to laying down the biorisk management infrastructure for the whole country, this project also helped identify future twins, says Will Pinard, a Sandia biorisk management expert also involved in the program.

“Back then, there were no books and very few courses, so most of what I know about biosafety I learned directly from other people.”

Omar Elahmer, from Libya’s National Centre for Disease Control and a member of the third Twinning class, originally planned to survey researchers and health care workers from throughout Libya about gaps in recent university graduates’ laboratory training. After designing the survey and receiving 450-500 responses, he saw there was a real need for basic biorisk management training. He worked with his twin, Angie Birnbaum, Tulane University’s director of biosafety, to design a basic curriculum based on what the surveys said would be most necessary before starting to work in a lab. Based on this project, the US State Department provided the funding to train 20 Libyan professors to teach biosafety.

“I’ve been fortunate to help a few twins. Their projects have ranged from the development of a project to address a site-specific biorisk need to projects that will serve as the foundation for biorisk management education of all laboratories in that country under their respective ministries. The latter is mind-boggling,” says Ben Fontes, a biosafety officer at Yale University.

Extensive network of biosafety professionals

The project’s results are only one product of the Twinning program.

“For me, the primary purpose of the Twinning program is to create this large network that’s going to survive for decades,” says Eric, adding, “The networking doesn’t just happen East-to-West. The networking happens within the region as well.”

Having a network of biosafety experts to ask for help when he had questions was critical when Eric started out as a biosafety officer 20 years ago. He says, “Back then, there were no books and very few courses, so most of what I know about biosafety I learned directly from other people.”

By involving biosafety experts from many different institutions, Eric is intentionally making the twin network as diverse and sustainable as possible. Some twins have experience with animal facilities, some with government research facilities, and many with universities. This increases the likelihood that someone within the network has experience with an unusual issue.

Another important outcome of the program is enhancing the credibility of biosafety as a profession around the world. Illustrating that biosafety can be a career instead of just extra hoops to jump through in the lab can prevent the spread of diseases to researchers and even reduce the chance that terrorists can gain access to hazardous biological agents, says Eric.

The US Department of State Biosecurity Engagement Program has funded five classes of Middle East and North Africa regional twins and two classes of African twins. The fifth Middle East and North Africa regional class will wrap up in mid-November. The first Defense Threat Reduction Agency-funded class will begin at the same time.

“The Twinning program has been the most gratifying program I’ve ever participated in,” says Melissa Morland, assistant director and biosafety officer at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, who has been a twin in every class since the beginning. “It is amazing to know that as part of this program, we are part of the progress that is being made in developing biorisk management around the world. I love to see the excitement of the twins as they are part of something new at their facilities and often in their home countries.”