There’s nothing typical about work at Sandia’s Tonopah Test Range

Tonopah Test Range’s Mark Gonzales is in the field before the sun ever peeks over the mountains that flank the range, readying equipment — some of it older than he is — for a flight test in the B61-12 weapon refurbishment program.

Test morning is a bit like riding a roller coaster: “You wake up bright and early just to wait in line. Once it’s finally your turn to ride and the roller coaster is beginning its climb, there’s a buildup of anticipation,” Mark says. Anticipation doesn’t come from a roller coaster’s clacking; rather, it builds with radio calls from the range controller and the pilot of a plane carrying a mock nuclear weapon.

Then the weapon releases, followed by a long, adrenaline-inducing moment as it falls.

“For that minute, everyone’s attention is on keeping their system — camera, telescope, radar, antenna — focused on that unit. Once that unit hits the ground, all that anxiety and excitement is swept away,” Mark says. “Just like that, it’s all over.”

At the 280-square-mile Tonopah Test Range, there’s no sense of the typical. Some days Mark might work on tasks for specific programs, like the latest flight test in March. Other days he might splice cable or fix damage done to remotely placed equipment by the hooves of wild horses and by the teeth of rodents who love Kevlar yarn insulation in fiber-optic cables to line their nests.

Tonopah: far from everything

“The biggest thing is how remote we are,” he says. The range is 255 highway miles, most of them two lanes, from Las Vegas. The closest community is 40 miles, the town of Tonopah, population not quite 2,500. Everything else between the isolated range and the glitter of Las Vegas is even smaller.

“There’s no Home Depot if you need something,” Mark says. “You make do with what you have to get the mission completed.”

A few dozen workers from Sandia, which runs Tonopah, and contractor Navarro Research and Engineering tackle whatever needs to be done. Sometimes the range’s Sandia staff members take extra schooling in areas outside their background because, as Mark points out, “there is no one else.”

Testing for the B61-12 Life Extension Program is accelerating, and range manager Brian Adkins predicts weeks of multiple tests. He has 22 people assigned to him, including five matrixed from other Sandia organizations. Extra people come in for tests, generally about 20 mission essential and 15 mission support staff.

But here’s the deal: Tonopah has one radar operator and three radars; one primary tracking telescope operator and three telescopes; one cinetheodolite operator and about a half-dozen of the optical instruments that track accuracy along a trajectory.

Brian gets extra operators from some of Navarro’s roughly 35 plumbers, carpenters, and electricians who are cross-trained for range duties that include helping position instruments, running a cinetheodolite, or operating recovery equipment when it’s time to dig a test unit out of the dirt.

Juggling duties is the norm

Mark illustrates how those at Tonopah juggle duties. He works communications and network issues, and Brian says he’s also learning new skills in telemetry. He’s part of two teams, communications IT and telemetry.

Born in New York, Mark at 27 has lived in Nevada half his life, since his family moved after his mother “went on vacation to Las Vegas and returned with a deed to a house.” He attended West Virginia University and later joined the Nevada Army National Guard. There, he got training on satellite communications, a natural background for signal acquisition and telemetry work at Tonopah. He picked up additional skills in information technology during a 2011 deployment to Afghanistan. Mark was still with the guard when he came to the range three years ago. His six-year enlistment was up last year.

On non-test weeks, Tonopah staff members work long hours crammed into a few days. On test weeks, they work even more days before getting a long weekend at home, which for most of the staff is Las Vegas. Since that schedule makes it impractical to drive home after work every night, Sandia and Navarro employees stay at a cluster of Tonopah dorms known as Man Camp. Working at the range, Brian says, is like being on travel every week.

Employees have their own permanent dorm room with a basic desk, bed, television, microwave, and small refrigerator, and they try to make it homey by rearranging the furniture or bringing books, their own sheets, perhaps a guitar. Mark keeps car magazines, pictures from home, a case of energy drinks, and a wardrobe that stays at the dorm since there’s a laundry room. Man Camp residents can eat at a range cafeteria a few miles away.

On a test day in March, Mark is up at 4 a.m. and in the communications shop an hour later, checking that a half dozen air-to-ground radios are functioning. That doesn’t take long, so it’s still dark when he drives a quarter-mile to Sandia’s Test Operations Center. The short distance is off Tonopah’s main two-lane road, meaning less worry about the potential road hazards of wild horses, pronghorn antelope, rabbits, and coyotes.

Moving from job to job during tests

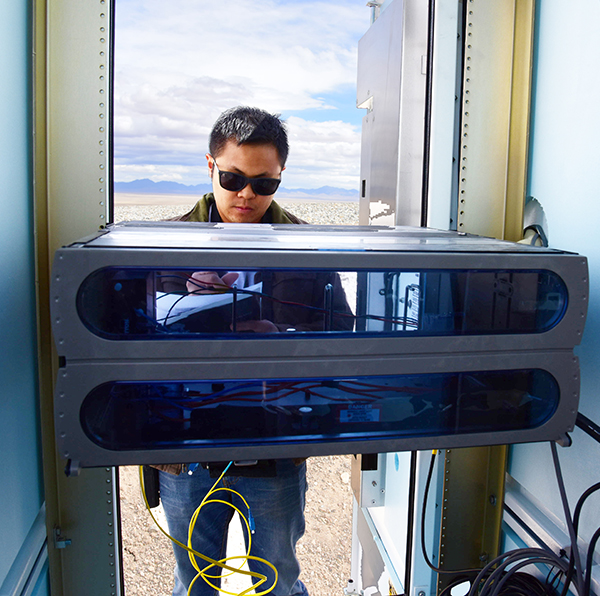

At the center, he prepares the telemetry ground station — powering up and logging into antenna control computers, receivers, and other systems.

Then much of the time until the test begins is spent on communication and integration checks by a team that includes the test director, range communications, telemetry, and others, Mark says. Communications checks verify that critical voice communications come in loud and clear. Integration checks make sure everything from telescopes to radar works and is synchronized with the Tonopah Range Acquisition and Control System, computers that collect and record radar information and retransmit it to the field so operators can orient their systems and focus cameras.

During the test, Mark works from the center’s telemetry lab, remotely operating antennas that track the mock test weapon from release to impact. Another operator runs another antenna from a mobile trailer miles away.

We’re kind of the final exam to send a grade to the president.

By 9:30 a.m., the test over, Mark remotes into a weather station about three miles away to track a small weather balloon carrying a radiosonde that collects information. Knowing the temperature, wind speed, humidity, and other conditions at various altitudes helps engineers correlate any anomalies in test data that could be weather-related, he says.

Weather balloon taken care of, he moves on to post-processing telemetry work, helping extrapolate and correlate data from instruments around the range for initial reports that indicate how the test went.

Mark’s day ends at 3:30 p.m. Since he’s not on the recovery team, his next job is working on legacy communications systems. Some equipment dates from the 1950s, and manufacturers no longer make or support it. The Tonopah staff must keep the system working and do upgrades when possible.

Improvements include fiber-optic network

Last year, the range laid fiber-optic cable that replaced a wireless network that couldn’t handle data demands anymore and copper cable that had been in place since Tonopah’s early days six decades ago. Mark likened the change to the computer world going from an old, slow modem to a gigabyte on the Ethernet.

Tonopah’s Lee Goodrich coordinated with the Air Force to bury the fiber-optics in trenches starting last spring. After the 2016 test season, Mark and communications/network technologist Chris Childers began splicing fiber-optics, laboriously connecting section after section. They worked from October through December, largely from a specially designed trailer towed from site to site. The March test was the first to use the new network.

Brian says the range has about five times as much work now as in 2012 and three fewer people. That’s why everyone takes on multiple jobs.

During the March test, chief engineer Glen Watts, Tonopah’s technical lead, ran a field sensor that was being tested for remote operation. Range photographer Jim Galli manned a tracking telescope. Sandia emergency medical technician Rob Elliott and Joe Leigh of Environmental Safety and Health prepared and launched the weather balloon that Mark tracked. Optical systems technologist Mark Skobel, who ran the remote antenna trailer, also helped run telemetry operations.

Brian says the technologist volunteered for special schooling, got training from experienced colleagues and found a mentor in Gary Kirchner. Gary is from Sandia/California but spends most of his time at Tonopah during test season.

Brian calls Tonopah a national asset for the nation’s nuclear stockpile.

“We test it here, analyze the data, and provide reports for the engineers to analyze. Eventually that all gets sent through the Department of Defense and Department of Energy chains,” he says. “We’re kind of the final exam to send a grade to the president.”