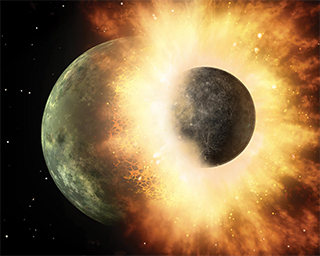

WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE — Sandia’s Z machine provides hard data on the surprisingly low amount of pressure required to metamorphose iron from a massive intrusive force to a gentle vaporized mist as astrophysical bodies collided in space during the later stage of Earth’s formation. That reduced pressure — 40 percent lower than formerly assumed by theoreticians — helps explain the splashes of iron in Earth’s mantle. This artist’s concept shows a celestial body about the size of our moon slamming at great speed into a body the size of Mercury. (Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Researchers at Sandia’s Z machine have helped untangle a long-standing mystery of astrophysics: why iron is found spattered throughout Earth’s mantle — the roughly 2,000-mile thick region between Earth’s core and its crust. It seemed more reasonable that iron arriving from collisions from planetesimals ranging from several meters to hundreds of kilometers in diameter, during Earth’s late formative stages, should have powered bullet-like directly to Earth’s core, where so much iron already exists.

A second, correlative mystery is why the moon proportionately has much less iron in its mantle than does Earth. Since the moon would have undergone the same extraterrestrial bombardment as its larger neighbor, what could explain the relative absence of that element in the moon’s own mantle?

To answer these questions, scientists led by professor Stein Jacobsen at Harvard University and professor Sarah Stewart at the University of California Davis wondered whether the accepted theoretical value of the vaporization point of iron under high pressures was correct. If vaporization occurred at lower pressures than assumed, a solid piece of iron after impact might disperse into an iron vapor that would blanket the forming Earth instead of punching through it. A resultant iron-rich rain would create the pockets of the element currently found.

As for the moon, the same dissolution of iron into vapor could occur, but the satellite’s weaker gravity would be unable to capture the bulk of the free-floating iron atoms, explaining the dearth of iron deposits on Earth’s nearest neighbor.

Looking for experimental rather than theoretical values, researchers turned to the capabilities of Sandia’s Z machine and its Fundamental Science Program, coordinated by Thomas Mattsson (1641). This led to a collaboration between Sandia, Harvard, UC Davis, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) to determine an experimental value for the vaporization threshold of iron to replace the theoretical value used over decades.

Rick Kraus at LLNL (formerly at Harvard University), and Sandia researchers Ray Lemke (1641) and Seth Root (1646) made use of Z’s capability to accelerate metals to extreme speeds using high magnetic fields. The researchers created a target that consisted of an iron rectangle 5 mm square and 200 microns thick, against which they launched aluminum flyer plates travelling up to 25 kilometers/second. At this impact pressure, the powerful shock waves created in the iron cause it to compress, heat up, and — in the zero pressure resulting from shock waves reflecting from the iron’s far surface — turn to vapor.

The result, published in Nature Geosciences on March 2 under the title “Impact vaporization of planetesimal cores in the late stages of planet formation,” shows the result: The shock pressure experimentally required to vaporize iron is approximately 507 gigapascals (GPa), undercutting by more than 40 percent the previous theoretical estimate of 887 GPa. Astrophysicists say that this lower pressure is readily achieved during the end stages of planetary accretion.

Emailed principal investigator Kraus, “Because planetary scientists always thought it was difficult to vaporize iron, they never thought of vaporization as an important process during the formation of the Earth and its core. But with our experiments, we showed that it’s very easy to impact-vaporize iron. This changes the way we think of planet formation, in that instead of core formation occurring by iron sinking down to the growing Earth’s core in large blobs (technically called diapirs), that iron was vaporized, spread out in a plume over the surface of the Earth and rained out as small droplets. The small iron droplets mixed easily with the mantle, which changes our interpretation of the geochemical data we use to date the timing of Earth’s core formation.”