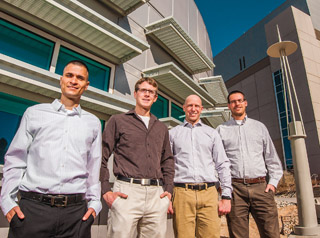

EARLY CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS — Sandians, left to right, Adrian Chavez (5629), Matthew Brake (1526), Seth Root (1646), and Daniel Stick (1725) will be recognized in a ceremony later this year as recipients of the Presidential Early Career Award for Science and Engineering (PECASE). The award is the highest honor the US government gives to outstanding scientists and engineers who are beginning their careers. (Photo by Randy Montoya)

Sandia researchers Matthew Brake (1526), Adrian Chavez (5629), Seth Root (1646), and Daniel Stick (1725) have been named by President Barack Obama as recipients of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE). The PECASE Award is the highest honor bestowed by the US government on outstanding scientists and engineers who are beginning their independent careers.

The four Sandians are among 102 researchers nationwide to receive the honor, and Sandia is tied with Princeton for the most PECASE recipients this year. All recipients were either funded by or employed by 13 federal agencies, including DOE. Winners will be recognized later this year at a ceremony in Washington, D.C., for their work in advancing the nation’s science and engineering.

Matthew Brake

Matt, a graduate of Carnegie Mellon University’s mechanical engineering program, joined Sandia in early 2008 after earning his PhD. One aspect of his work focuses on understanding interfacial mechanics, or how two objects interact when they impact and rebound. “You want to be able to predict how a joint will perform in different shock environments. You could build a mesh and have thousands and thousands of degrees of freedom, but to simulate that with the necessary number of elements to get convergence for your contact models, it’s going to be prohibitively expensive. There’s no way to actually do that in a feasible amount of time and get the correct answer,” Matt says. “So the whole philosophy behind this modeling effort is rather than having the extremely large number of elements needed to get convergence, why don’t we use a course mesh, but have a very high fidelity representation of contacts, so we can very quickly and accurately do these simulations of how a strong link will respond in different environments.” Shrinking the models means an analyst can now understand in a few days with a desktop what would have otherwise taken years on a supercomputer.

Matt is currently studying friction and energy dissipation between two bodies and has become involved with the global community of joints researchers, taking on several leadership positions. He is the secretary of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and is also organizing the 2014 Sandia Nonlinear Mechanics and Dynamics Summer Research Institute, which will bring researchers from around the world to Sandia to study some of the biggest challenges of predicting the behavior of jointed structures.

Adrian Chavez

Adrian, an Albuquerque native, started at Sandia in 2000 as an intern in the Center for Cyber Defenders while a student at the University of New Mexico. He spent four years there, learning about computer security. In 2004, he took advantage of Sandia’s Master’s Fellowship Program to pursue his master’s degree at the University of Colorado, Boulder and returned to Sandia in 2006. Since that time, he has focused on cybersecurity for critical infrastructure systems and adding security to systems like the power grid, oil and gas refineries, and water pipelines to make sure that responses and protections are in place in the event of a cyberattack. Adrian has worked on several projects focused on securing these systems.

“The vision of each project is to secure the hardware and software of critical infrastructure systems that harness our nation’s most critical assets. My research focuses on retrofitting new security protections into an architecture that supports both the legacy and modern devices,” Adrian says. “Protections that were previously unavailable in these systems include end-to-end cryptographically secure communications, secure engineering access, and built-in situational awareness.”

Building on that model, Adrian and his team are working on randomizing networks, essentially turning computer networks into moving targets, making it more difficult for an adversary to locate and attack a specific system.

“I am honored to receive this award. It’s great to have all of the excellent research we perform at Sandia be recognized at such a high level,” Adrian says. He is working on his doctorate in computer science at the University of California, Davis and is interested in continuing research to help secure critical infrastructure systems.

Seth Root

Seth earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics at the University of Nebraska and his doctorate in physics from the Institute of Shock Physics at Washington State University. He joined Sandia in 2008 for the opportunity to work on the Z machine, the world’s largest pulsed-power facility.

“You are working on a platform that can generate pressure and temperature regimes that few else in the world can access to understand material behavior at extreme conditions,” he said. “The opportunity to do research at extreme conditions at a facility like Z is really exciting.”

Seth has been involved in a team combining theoretical and experimental methods. The team is applying density functional theory, a method of calculating energies and pressures using quantum mechanics, to noble gases — which are odorless, colorless, and chemically inert under standard conditions — at extreme pressures and high temperatures. In one experiment, the physicists cryogenically cooled xenon gas to a liquid and then shock-compressed it to 8 million atmospheres of pressure. “We were able to show that density-functional-theory simulations can capture the response of the liquid xenon at very high pressures,” he said. The research helps explain the physics of atoms with relatively high numbers of electrons and has helped to verify and improve theoretical methods used in computer simulations.

Seth says the PECASE was more than just an individual award, but rather a recognition of the many people involved. “We have a really good team at Sandia. The award shows that the work we do in understanding material properties at high pressures is greatly appreciated on a national level,” he says.

Daniel Stick

Dan earned his undergraduate degree in physics from the California Institute of Technology and his PhD at the University of Michigan. He was nominated for his development and demonstration of miniaturized ion traps for quantum computing. Moore’s Law predicts that about every 18 months the processing power of classical computers double, but as devices shrink, they will run into fundamental physical limits at which transistors start behaving unpredictably. Quantum computing is one strategy to circumvent these limitations, but there is a lot of work to be done.

“For these devices to be a viable platform for quantum information processing, they have to be made more reliable and be engineered to eliminate particular sources of noise that make quantum computing extremely difficult,” Dan says. “Quantum computing is something that is usually talked about in terms of its promise for exceeding classical computing, but everyone realizes that the technical challenges for actually realizing such a device are extraordinary.”

Dan came to Sandia as a postdoctoral researcher in 2007 and was hired on as a staff member two years later. With his background in experimental atomic physics, he worked with Sandia’s microfabrication experts to design and fabricate novel trap geometries.

“My main contribution is the experimental demonstration of these traps. They’ve become really successful in that a lot of the leading ion-trapping groups around the world use Sandia-fabricated ion traps for their quantum experiments,” Dan says. “This award is a wonderful recognition, and I’m honored to receive it. There are so many people at Sandia who deserve some of the credit for this as well.”

Three of the four winners, Matt, Dan and Adrian, were or are supported by LDRD funding. The awards were established by President Bill Clinton in 1996 and coordinated through the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the Executive Office of the President. Awardees are selected for their pursuit of innovative research at the frontiers of science and technology and their commitment to community service as demonstrated through scientific leadership, public education, or community outreach.