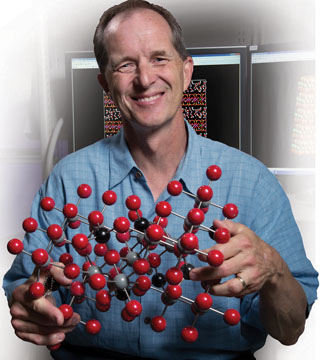

Randy Cygan (6910) says molecular modeling sheds light on how a waste repository might perform. “It allows us to develop performance assessment tools the Environmental Protection Agency and Nuclear Regulatory Commission need to technically and officially say, ‘Yes, let’s go ahead and put nuclear waste in these repositories.’” (Photo by Lloyd Wilson)

Radioactive waste disposal can worry people. They want to know where contamination might end up and how it can be kept away from drinking water.

“Very little is known about the fundamental chemistry and whether contaminants will stay in soil or rock or be pulled off those materials and get into the water that flows to communities,” says geoscientist Randy Cygan (6910).

Researchers have studied the geochemistry of contaminants such as radioactive materials or toxic heavy metals like lead, arsenic, and cadmium. But laboratory testing of soils is difficult. “The tricky thing about soils is that the constituent minerals are hard to characterize by traditional methods,” Randy says. “In microscopy there are limits on how much information can be extracted.”

Randy says soils are dominated by clay minerals with ultra-fine grains less than two microns in diameter. “That’s pretty small,” he says. “We can’t slap these materials on a microscope or conventional spectrometer and see if contaminants are incorporated into them.”

Randy and his colleagues are instead developing computer models of how contaminants interact with soil and sediments. “On a computer we can build conceptual models,” he says. “Such molecular models provide a valuable way of testing viable mechanisms for how contaminants interact with the mineral surface.”

He describes clay minerals as the original nanomaterial, the final product of the weathering process of deep-seated rocks. “Rocks weather chemically and physically into clay minerals,” he says. “They have a large surface area that can potentially adsorb many different types of contaminants.”

Clay minerals are made up of aluminosilicate layers held together by electrostatic forces. Water and ions can seep between the layers, causing them to swell, pull apart, and adsorb contaminants. “That’s an efficient way to sequester radionuclides or heavy metals from ground waters,” Randy says. “It’s very difficult to analyze what’s going on in the interlayers at the molecular level through traditional experimental methods.”

Molecular modeling describes the characteristics and interaction of the contaminants in and on the clay minerals. Sandia researchers are developing the simulation tools and the critical energy force field needed to make the tools as accurate and predictive as possible. “We’ve developed a foundational understanding of how the clay minerals interact with contaminants and their atomic components,” Randy says. “That allows us to predict how much of a contaminant can be incorporated into the interlayer and onto external surfaces, and how strongly they bind to the clay.”

The computer models quantify how well a waste repository might perform. “It allows us to develop performance assessment tools the Environmental Protection Agency and Nuclear Regulatory Commission need to technically and officially say, ‘Yes, let’s go ahead and put nuclear waste in these repositories.’”

Molecular modeling methods are also used by industry and government to determine the best types of waste treatment and mitigation. “We’re providing the fundamental science to improve performance assessment models to be as accurate as possible in understanding the surface chemistry of natural materials,” Randy says. “This work helps provide quantification of how strongly or weakly uranium, for example, may adsorb to a clay surface, and whether one type of clay over another may provide a better barrier to radionuclide transport from a waste repository. Our molecular models provide a direct way of making this assessment to better guide the design and engineering of the waste site. How cool is that?”