With more than 137 million artifacts, the Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum and research complex. It comprises a mind-boggling scope of treasures, representing America’s rich heritage, art from around the globe, and the immense diversity of the natural and cultural world.

This month, nine historically significant robots from Sandia are joining the collection, where they will be permanently housed in the National Museum of American History, home of more than 3.3 million pieces of US history, including the wool and cotton flag that inspired the Star Spangled Banner, Kermit the Frog, and the desk Thomas Jefferson used to draft the Declaration of Independence.

“For the Smithsonian to request Sandia technology to be in their collections is an external recognition of the significance of Sandia National Laboratories’ contributions to the nation,” says Philip Heermann (6530) senior manager of Intelligent Systems, Robotics and Cybernetics and participant in the signing ceremony at the museum. “These robots will be in the same collections as some of Thomas Edison’s first electric light bulbs and Samuel Morse’s original experimental telegraph. The Smithsonian selected Sandia robots for inclusion after they researched the history of robotics and they found worldwide references, all pointing back to Sandia Robotics as early pioneers. The Sandia robots are similar to Edison’s electric light bulb in that both are first steps and testaments to American innovation.”

MARV, the tiny marvel

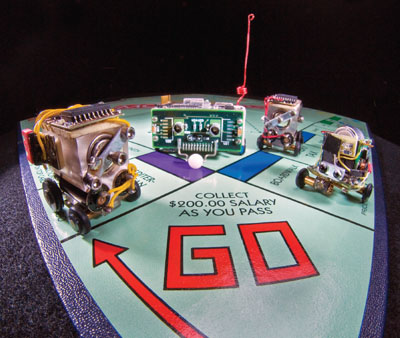

A Smithsonian curator contacted Sandian and former robotics engineer Ray Byrne (5535) earlier this year about obtaining some of the MARV, or Miniature Autonomous Robotic Vehicles, that made headlines in the mid-1990s as one of the first miniature robots developed in the US. Taking up no more than one cubic inch of space, MARV housed all necessary power, sensors, computers, and controls on board. Such an accomplishment held promise for exciting future developments and applications for medicine and the military.

Retired Sandia robotic senior scientist Barry Spletzer, who was instrumental in creating MARV and the Hopper, spoke at the transfer ceremony about the significance of the robots.

“Nothing like MARV had ever been built before,” Spletzer says. “We never expected recognition and certainly never thought we’d end up in the Smithsonian. This is certainly a career achievement.”

As the Smithsonian soon found out, MARV was just the tip of the iceberg of Sandia’s contributions to the advancement of the robotics field.

“The curator said they were looking for anything of historical significance. We have a lot that fit that requirement, so I started mentioning all of these older robots, and she was very interested,” Ray says. “So far, we’ve donated Dixie, the first battlefield scout robot, SIR, one of the first truly autonomous interior robots, the hopping robots, the NETBOTS, MARV, and the descendants of MARV, the super-miniature robots.”

The Sandia Interior Robot, or SIR, made a lasting impression on the nation when it was introduced in 1985 as the first truly autonomous interior robot. At the time, SIR was the only robot able to navigate a building without a preprogrammed pathway or floor wiring to find its way. It could run in manual or autonomous modes using navigational software, also developed at Sandia. SIR could perform dangerous work, such as disposing of radioactive waste or reconnaissance in a hostile environment.

In 1987, Sandia unveiled Dixie, the first battlefield scout robot. The all-terrain vehicle could perform reconnaissance work and exploration missions in a variety of landscapes. Dixie uses teleoperation with advanced navigation aides to enhance a remote operator’s understanding of surrounding terrain. The Hopper made news when it debuted in 2000 for its unique ability to navigate over walls and other obstacles by hopping 20 feet in the air over them.

With applications for planetary exploration, gathering war-fighting intelligence, and assisting police during standoffs or surveillance operations, the Hopper was the first robot powered by a combustion cylinder and a piston foot, and the wheeled Hopper was the first hybrid hopping/wheeled mobility system.

Sandia continued to wow the robotics field with the introduction of “superminature robots” in 2001. These tiny robots descended from MARV and were built small enough to be able to scramble through pipes or buildings to look for human movement or chemical plumes. Less than a quarter-cubic-inch in size, these robots could “turn on a dime and park on a nickel” and could include such enhancements as a miniature camera, microphone, communication device, and chemical microsensor. They had the ability to communicate with one another and work together, much like insects in a swarm. The superminiature robots were selected by Time as the invention of the year in robotics in 2001.

The related NETBOTS are roughly the size of a remote-controlled toy car, and in fact, built on the same platform. With more than 20 vehicles in the group, at the time they comprised the largest team of cooperating small robots ever developed. They could communicate and localize with respect to one another. NETBOTS operated on a network that allowed vehicles to pass messages and camera images to other vehicles out of the line of sight, and had applications for military and explosive ordinance removal. Ray took all of the robots on the plane, either in carry-on or checked luggage, to Washington, D.C., for a transfer ceremony to kick off the museum’s festivities for National Robotics Week.

“These are historically significant,” Ray says. “I am pleased that the Smithsonian has chosen to recognize Sandia’s contribution to robotics.”