In a day that highlighted Sandia’s up-and-running Red Storm supercomputer — the fastest in the world in two critical benchmark tests, if not in raw speed — NNSA Administrator Linton Brooks told members of the media that the DOE/NNSA weapons complex is “on the verge of making some fairly major changes in the way we maintain the safety, security, and reliability of the nuclear weapons stockpile.”

“We’re looking toward a smaller, transformed stockpile that is based around a concept called the reliable replacement warhead,” Brooks said during a Feb. 8 media event in the Vislab in Sandia’s Joint Computational Engineering Lab. The RRW concept, he said, hinges on responsive infrastructure and production and design capabilities.

“We can think about these dramatic advances,” Brooks said, because of the high quality of the talent at Sandia and the other weapons labs — and because of the availability of modern computers.”

Labs Director Tom Hunter, who introduced Ambassador Brooks to reporters, lauded NNSA for its role in funding and supporting investment in advanced computing. Red Storm and its sister computers at other NNSA labs, Tom said, are enabling a much-needed “reengineering of engineering” for the 21st century.

“In terms of raw speed in computing,” Tom noted, “of the top six supercomputers in the world, the NNSA now has five and two of them are at Sandia [Red Storm and Thunderbird].”

With the power of the new generation of computers, Tom noted, scientists and engineers can “look at phenomena we were unable to do even a few years ago.”

Tom cited the role of “some brave thinkers almost two decades ago,” including many Sandians, whose vision of massively parallel computing and the ability to link thousands of processors to work simultaneously to solve huge problems has been fully vindicated.

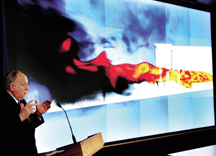

Using the stunning graphics display capabilities of the JCEL Vislab, Tom showed two visualizations showcasing Red Storm’s extraordinary capabilities. The first, showing the results of a 10-megaton nuclear blast to destroy an asteroid that may be on a collision course with Earth, depicts in vivid detail the asteroid coming apart and scattering into space in smaller (less dangerous) pieces. The second visualization, a sophisticated simulation of a fire event involving a nuclear weapon, showed streaks of fire racing across the giant Vislab screen. Tom emphasized that the videos were not animations (such as might be produced by a movie studio), but were true simulations derived from the physics of the phenomena being studied, simulacra of real-world events. There was, in short, a deep reality behind the beautiful images.

Ambassador Brooks, picking up on Tom’s theme, said, “When I grew up, there were two ways to think about science: theory and experiment. Some of my colleagues in the scientific community now say that scientists in the future will grow up thinking there is theory, there is experiment, and there is simulation — three ways in which we advance scientific knowledge.

If that turns out to be true — and it probably will be — it will be the result, in part, of the kind of spectacular successes in simulation that you saw [in the visulazations].”

Brooks said the new era of supercomputers is the result of strategic decisions made at DOE. “A decade ago, we sat down as a community [i.e., weapons complex policy leadership] and said that we needed — in order to truly conduct the kind of simulation we wanted — to improve the state of the art in computing by a factor of a million.

“A factor of a million in anything is pretty spectacular; in fact we’ve done that in computing. And we tout that a lot in terms in terms of the physics of weapons, but it’s equally important in the terms of basic safety and reliability, a part of the program that Sandia works on.”

In discussing Red Storm’s specific capabilities, Brooks noted that it performs 36 trillion operations a second, “a number that would have been inconceivable 20 years ago and regarded as a very considerable stretch even 10 years ago.”

Noting that references to supercomputers often discuss just the raw speed — 36 teraops in the case of Red Storm — Brooks offered a more refined perspective.

“There are a series of so-called high-performance computing challenge benchmarks, and Red Storm was designed to focus on two issues. . . .”

In the two “bottleneck issues” it was designed to address — the efficiency in which the 10,000+ processors are connected and the speed with which the processors can access memory — Red Storm is now the fastest computer in the world.