No matter what you do, don’t take your first ‘vomit comet’ ride on a full stomach

If — 32 times over a two-hour period — food or liquid in a human stomach is accelerated upward and then downward, experiencing two G’seach cycle and free fall at each upper changeover, a gastronomically unpleasant situation may occur, interpreted by stomach and brain as a mandate to retch.That is the situation facing Sandia student intern Jason Brown (1812) and three other chemical engineering students from the University of New Mexico when they ride NASA’s KC-135A air-plane on March 29-30 to learn whether a viscous polymer coating applied to a spinning silicon wafer can be deposited more smoothly in zero gravity than it can be on Earth.

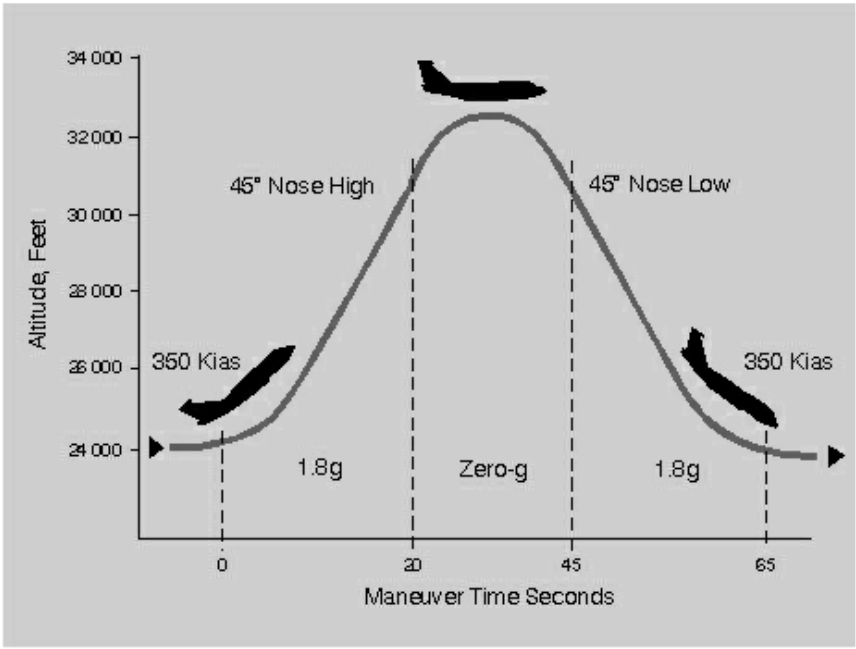

“This,” Jason says, “is the ultimate roller coaster. And I love roller coasters.” The gutted, former stratospheric-tanker refueling plane they will ride over the Gulf of Mexico climbs on a 45-degree angle that resembles (photographed just above the clouds) a passenger plane making an eerie break for freedom. The plane goes weightless near the pinnacle of its parabolic arc for about 30 seconds, when experiments must take place, and then accelerates downward before rising again. The four college students, riding in pairs, will get 30 passes of weightlessness on each flight, along with one arc approximating the gravity of the Moon and another of Mars.

Jason and co investigating UNM student Kelly Kuhn readily agree that “Being All You Can Be” is not usually part of the reason people study chemical engineering, but say their class is dedicated to changing the image of chemical engineers from“little guys with calculators and pocket protectors.” “Of course, we expect to write a paper on this,”says Kelly, who also admits she is debating whether to swallow a NASA-offered anti-nausea pill that will settle her stomach but might slow her thinking.The KC-135A ride is popularly referred to as the “vomit comet” because about 60 percent of riders on these flights experience nausea. Similar intermittently weightless flights have been used by NASA in support of most of its major space initiatives. What will happen to the coating at zero gravity is unknown and of scientific interest, agree Jason’s mentor Steve Thornberg (l812) and spin coating guru Tony Farino (1746).

Steve provides technical guidance and helped obtain corporate support for the proposal that NASA accepted; Tony provided the students the necessary test equipment. The students — who also include Doug Peters and Bill Jackson, with Tom Gamble as backup — will vary the wafer’s spin speed, coating thickness, and rate of deposition. The results will be com-pared with identical tests run earlier in Earth’s gravity. The researchers may find that gravity makes no difference to the evenness of deposit. Or they may find that the absence of gravity means the coating won’t adhere at all but instead just floats off. Or they may . . . just may. . . help define parameters from which abetter quality coating can be made.There are other reasons for going.

The UNM-based, Sandia-backed group won one of NASA’s 16 slots for student experiments — heavily competed for among hundreds of college student teams — partly because they intend to build on their already-demonstrated activism. “We plan to take videos and pictures of us floating, and after we come down, visit grade schools to show kids that science can be exciting,” says Jason.But the golden fleece of Jason and the other Argonauts is to form better coatings on their spinning silicon wafers. To achieve this, the self-named Spin Doctors have “ruggedized” their equipment by installing a metal frame around their plastic work bench.

They secured the analytic equipment to the bench,installed bolt brackets to attach the table to the floor of the plane, completely covered the top of the spin coater’s hood to prevent unwanted expulsions of material during weightlessness, and are considering changing plastic hood hinges to metal. They will have eight days of training in Houston before going up with their project,and will bring their prized results — which in size,shape, and luster resemble music CDs — back to Sandia for analysis.Steve, who’ll be at NASA’s Ellington Field dur ing the flight, hopes he doesn’t hear any radio mes-sage announcing, “Houston, we have a problem.”But he’s happy with the project. He says that the science of the trip is right in line with Sandia’s basic mission in semiconductors and the Laboratories’ long-standing support and encouragement of students, which is why Sandia corporately sponsored the UNM proposal to NASA.Also helping are Sandia High School students Cindy Stallard and Jessica Saunders. The title of the student experiment is “Study of Polymer Spin Coating for Photolithographic Semiconductor Development in Space.”