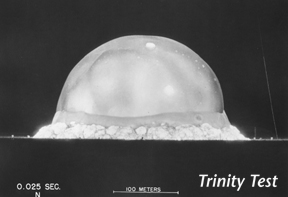

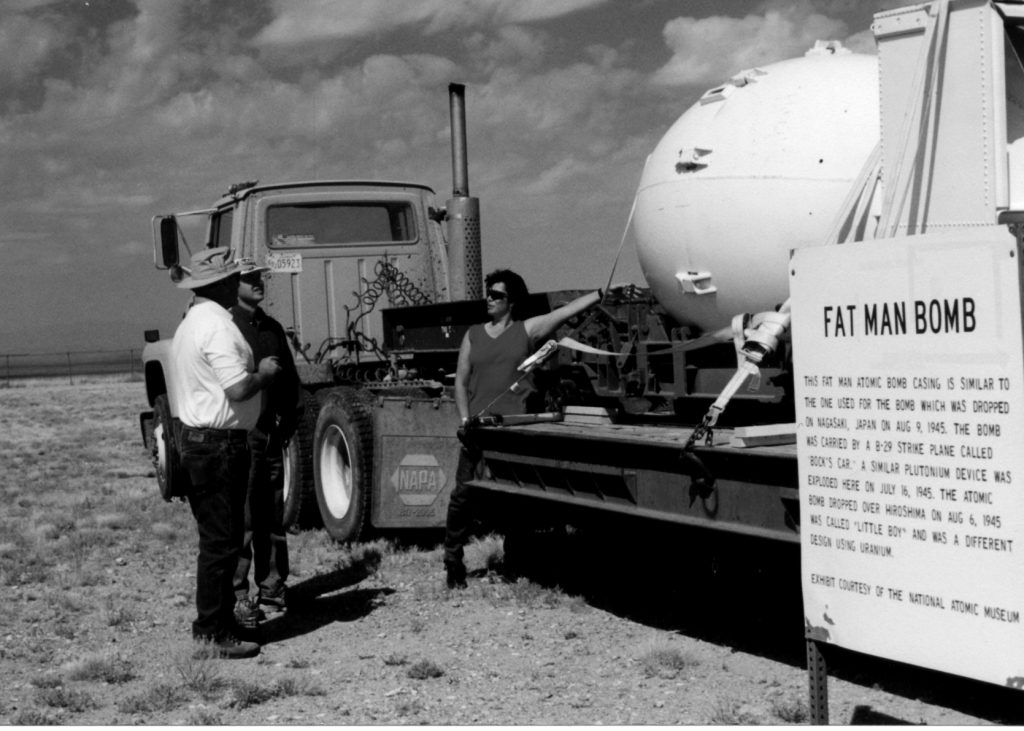

The blast that lit up the entire New Mexico sky at 5:29:45 a.m. on July 16, 1945 was “brighter than 20 suns and the most spectacular sunrise ever seen.”

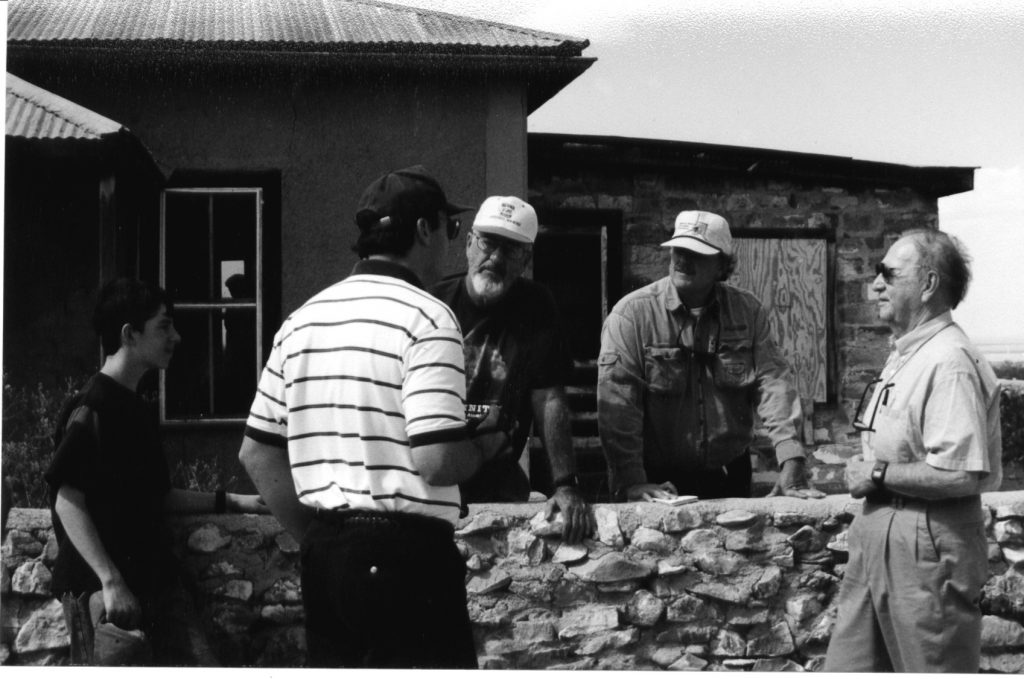

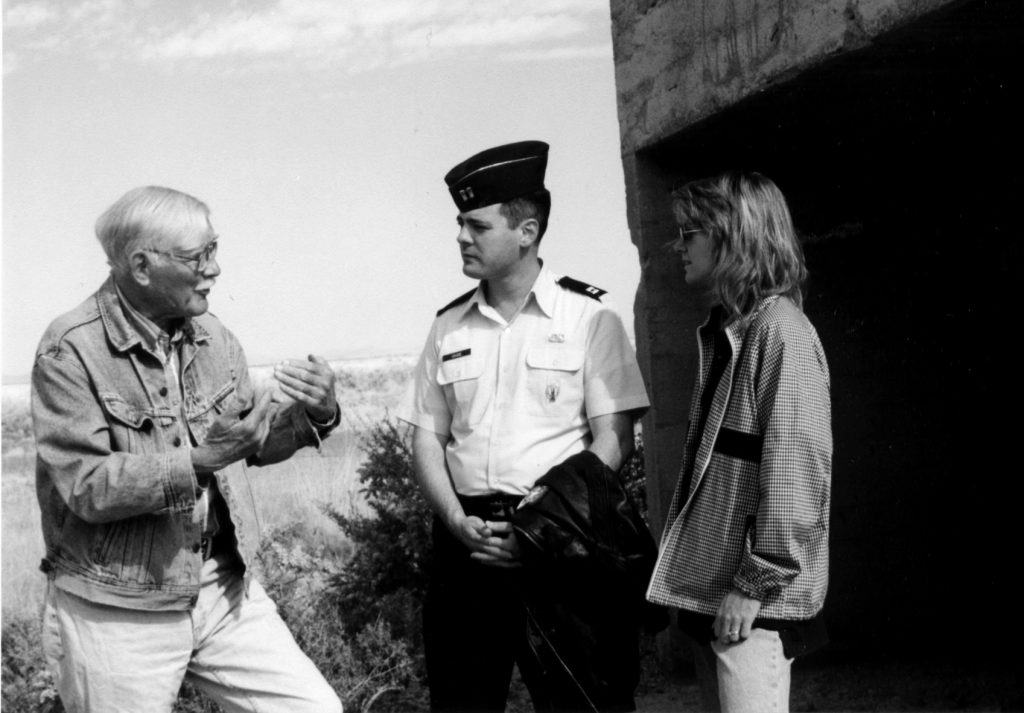

The group — which consists of young scientists and engineers who participate in an intense two-year program designed to give them a broad, in-depth understanding of nuclear weapons — received a personalized tour last month of the Trinity Site with Ben as their guide. It was one of many field trips the interns make to historical sites important to the country’s nuclear weapons program. Ben works with the group regularly as a mentor and instructor.

In 1945 Ben was a 22-year-old Army sergeant assigned as a technician to the photo-optical division in the Manhattan Project. Selected for the job because of his earlier work in industry making lenses and prisms, he was one of a handful of people in the division responsible for photographing the blast using both still and motion picture cameras.

On the tour Ben took the interns to the Trinity Base Camp where he first arrived in March 1945, joining some 200 soldiers, scientists, and technicians to prepare for the test.

The camp, Ben recalls, was built on the remains of a ranch on the Alamogordo Bombing Range, now the White Sands Missile Range. The old ranch house was in good repair and was given to the photo-optical division for headquarters. The testing of cameras and film processing took place there.

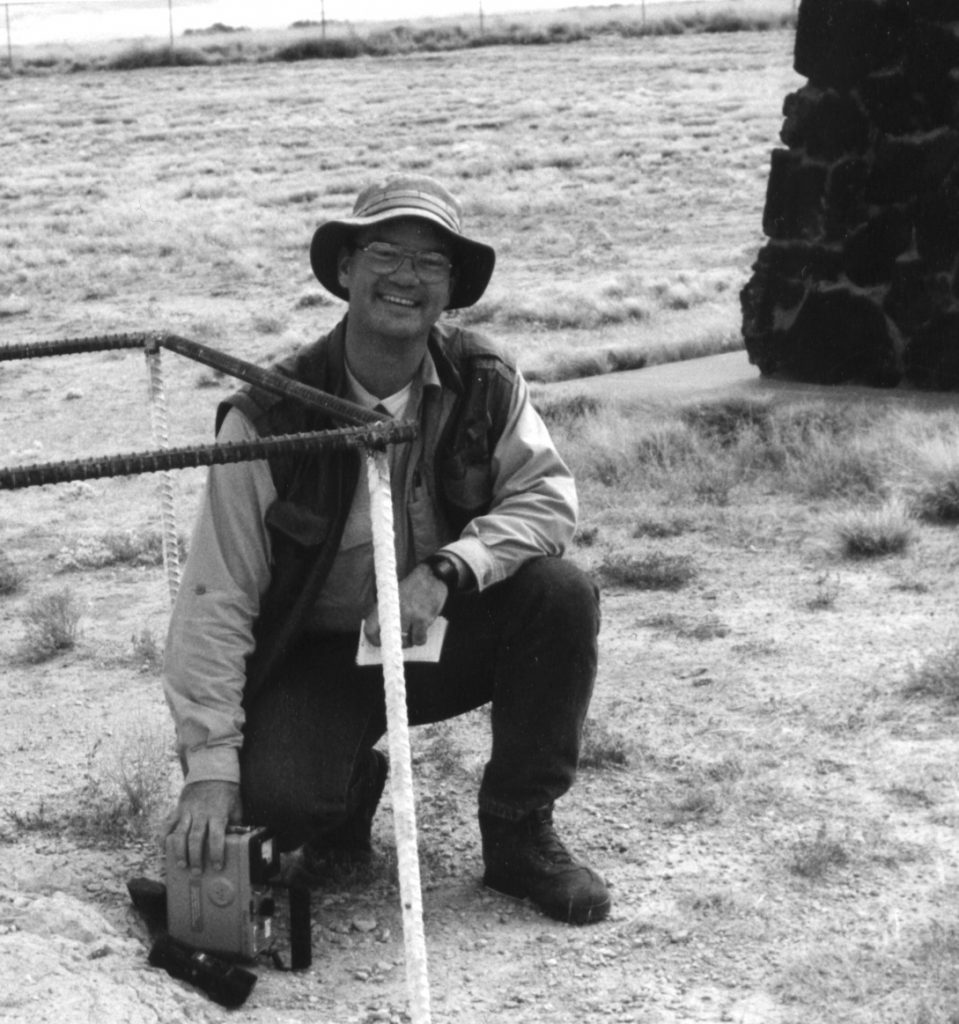

Ben and the interns also visited the McDonald Ranch, where the core of the bomb was assembled; “Ground Zero,” the location where the bomb — always referred as “the Gadget” — was exploded; and the concrete bunker six miles west of Ground Zero where some of the optics division’s cameras were placed to record the blast. He pointed to two other monitoring stations, one six miles south that served as the control station and another six miles north, a photo station.

Ben says the atmosphere at Trinity during those few months leading to the test was “one of dedication and hard work.”

“We knew we had a chance of shortening the war,” he says.

“Everything was so secretive,” he recalls. “Life was almost like living in a prison camp. We couldn’t leave, couldn’t telephone anyone, and our letters were censored.” Ben — working with his boss Julian Mack, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin, and others in the photo-optical group — set up many 35-millimeter motion picture cameras, a spectrograph, and several still cameras at the western monitoring station built in a concrete bunker. The experiments were designed to capture the explosion on film for future scientific study.

“We knew there would be a ball of fire that would rise and we arranged the cameras to follow it,” Ben says.

The day of the actual test started out with an early morning thunderstorm. The storm delayed the test from its originally scheduled time of 4 a.m. until nearly 5:30 a.m. Five seconds before the blast, an electronic pulse went out to a switchbox in the optics bunker. It was the signal to turn on the cameras. After switching on the cameras, Ben put a piece of welder’s glass up to his eyes to protect them from the bright light that was expected to come. Ben saw a ball of fire rise from the ground, creating a brilliant glow that lit up the dark sky brighter than the sun. “There was the bang and then the roar. The sound reverberated off the mountains,” he recalls. “With the sound came the shock wave — a high wind after the glow, almost strong enough to knock a man down.”

As the desert sky became illuminated with the unnatural ball of fire, Ben turned to his boss, Julian Mack, and said, “My God, it’s beautiful.” Julian came back instantly and replied, “No it’s terrible.”

Ben was thinking of the obvious success of the test. Mack was thinking of the moral implications.

Evidence of the power in the blast could be seen in some of the moving and still pictures the optics team took.

“The light was so bright that the first pictures taken by the cameras were overexposed,” he says. “Some film was even burned by the brightness of the light.”

But many of the pictures turned out perfect and provided significant scientific information that allowed scientists to fully analyze the blast.

Today, a lava rock obelisk that commemorates the Trinity Site as a National Historic Site marks Ground Zero. It was at this obelisk that the interns clamored to be photographed with Ben, one of the few people still alive who had a front row seat to the world’s first atomic explosion.

Ben sees the Trinity test as the paving the way for shortening World War II and saving many American and Japanese lives. The Trinity Test was conducted July 16, followed by the bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and Nagasaki on Aug. 9. The war was over on Aug. 15, VJ Day.

“Trinity was the proof test of what might be the greatest scientific achievement of all time. I was fortunate to have had a small part to play,” he says.

Last modified: November 3, 2000